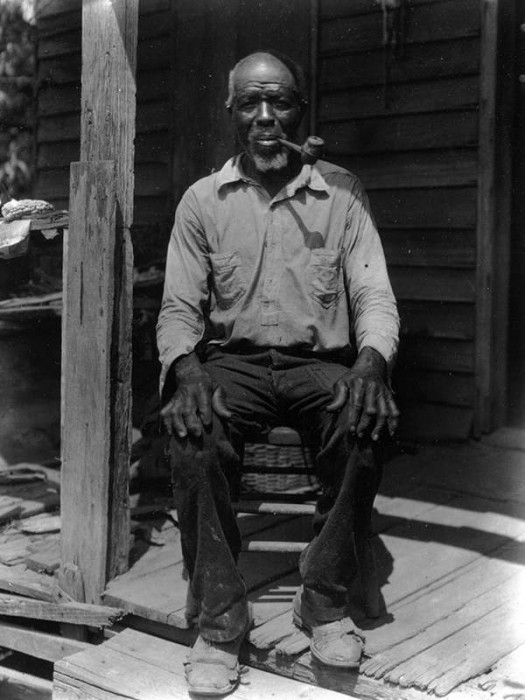

Born in Africa as Oluale Kossula, he died in America in 1935 as Cudjoe Lewis.

Ouale Kossula was considered the last person born in Afrika to have been enslaved in the United States. However, he was the last male survivor of the American slave ship, the Clotilda, which took captives from Africa to America in 1860. Kossula died on July 26, 1935, about 94 years of age. Four years before his death he narrated his story to Zora Neale Hurston, but when Hurston submitted the story to publishers in 1931, no one wanted to publish it, partly based on the fact that she wrote Kossula’s story, in his dialect.

Hurston who spent three months interviewing Kossula stated that when she had first hailed him by his Afrikan name, it brought tears of joy to his eyes. When she told him she wanted to hear his life story, she wrote, “His head was bowed for a time. Then he lifted his wet face: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’” Hurston also wrote that Kossula was, “The only man on Earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has 67 years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.”

Kossula was born in the modern West African country of Benin to Oluale and his second wife Fondlolu. He was the second of four children and had 12 step-siblings. He was a member of the Yoruba people, more specifically the Isha, whose traditional home is in the Banté region of eastern Benin.

At 14, Kossula began training as a soldier. He was also inducted into the Oro, a secret Yoruba male society whose role was to police and control society. At age 19, he fell in love with a young girl he saw at the market, and at his father’s urging underwent initiation that enabled young men and women to get married.

In April 1860, in the midst of his training, the army of the King of Dahomey, attacked the town, killing the king and many of the people, and taking the rest as prisoners. Kossula recalled: “I call my mama’s name. I beg the men to let me go find my folks. The soldiers say they got no ears for crying.” As he is led away, he sees in the hands of the Dahomey warriors the severed heads of his people. He watched them smoke the heads so they don’t spoil in the heat: “We got to set dere and see de heads of our people smokin’ on de stick.”

Kossula was taken to the port of Ouidah together with more than a hundred other captured people. After three weeks in the barracoon, he was sold. “De whyte man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose.” When he was brought on the Clotilda, he and the others were stripped of their clothing: “I so shame! We come in de ’Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage.”

Kossula endured a terrifying journey “of thirst and sour water,” across the Atlantic which seemed to “growl lak de thousand beastes in de bush”. The Clotilda, the last recorded slaver to the United States, arrived in Mobile, Alabama on Sunday July 8, 1860, under the cover of night, because by this time the importation of captives had been illegal in the United States for nearly 52 years. According to some accounts, Captain Tim Meaher of Mobile, Alabama, had bet a northern businessman $100,000 that he could smuggle a “cargo”, into America despite the ban.

While police were alerted to the illegal shipment, and charged Meaher with illegal possession of captives, by the time they arrived on his property to execute the arrest, he had hidden away the captives and had erased all trace of them having been there. Meaher owned an area of land outside Mobile called Magazine Point that was surrounded by swamp and only easily accessible by boat. This bought him time to hid his newly captured people from the lawmen. Without the physical evidence of the captives, the case was dismissed in January 1861, and Kossula and his fellow captives were forced to work as de facto enslaved people of Meaher, his brothers, or their associates. Kossula was purchased by James Meaher, for whom he worked as a deckhand on a steamer. During this time he became known as “Cudjoe Lewis.” He later explained that he suggested “Cudjoe,” a day-name commonly given to boys born on a Monday, as an alternative to his given name when James Meaher had difficulty pronouncing “Kossula.”

According to Kossula, on 12 April 1865, “De Yankee soldiers dey come down and eatee de mulberries off de trees. Dey say, ‘You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo’. “We so glad we makee de drum and beat it lak in de Affica soil.”

After they were freed, Kossula and his people requested repatriation to Afrika, and attempted to raise enough money for the voyage back home to their respective communities. When this proved difficult, Kossula who continued to work in Meaher’s lumber mill, eventually raised enough money to buy a two-acre plot of land in Magazine Point for $100 in 1872. The new community he helped to build was called Africatown, now known as Plateau, in Mobile, Alabama. Kossula became a respected leader in the community, the sexton of the church they built, the “Uncle Cudjo”, to whom people came seeking wisdom, asking for “a parable”. He even had meetings with prominent people such as Booker T. Washington.

Kossula married a woman who had also been on the Clotilda, Abila, and they had five sons and one daughter. To mark their attachment to their culture, they gave each of their six children an Afrikan name “because we not furgit our home”, and an American name that wouldn’t “be too crooked to call”. Sadly, five of the children died through illness or accident.

By the early 1920s, all his ship-mates from the Clotilda had passed away, leaving him as the only survivor out of the 116 Afrikans who had formed the “cargo”. During the last years of his life, he achieved some fame when writers and journalists interviewed him and made his story known to the public. But it was only Zora Neale Hurston who took the time and trouble to let him tell the full, book-length story of his life.

“After 75 years, he still had that tragic sense of loss. That yearning for blood and cultural ties. That sense of mutilation. It gave me something to feel about.” Zora Neale Hurston

During his interview in 1928 with Hurston, she made a short film of Kossula, which is the only moving image that exists in the Western hemisphere of an Afrikan transported through the transatlantic Maafa traffick. Kossula had always wanted to go back home. He told Hurston, “I lonely for my folks.” However, he was buried among his family in the Africans’ cemetery that opened in 1876. Today, a tall white monument marks his grave.

Kossula’s biography, entitled, Barracoon:The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston, was finally published in May 2018.

Source:

http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org-face/Article.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/barracoon-cudjo-lewis-zora-neale-hurston-last-slave-ship-survivor-book-life-story-published-a8335776.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/dec/19/zora-neale-hurston-study-of-last-survivor-of-us-slave-trade-to-be-published

The Story of Cudjo Lewis — The Last Living Slave Brought To America

3 comments

Thank you for this history.

THIS IS AN AWESOME PIECE! The National Geographic channel or The Smithsonian channel presented this piece during Black History Month. Thank you so very much for repeating it. Our young people need to know this as 1935 was only 83 yrs ago, and our “slave roots” are still very close to the surface.

Thank you for this informative and heart wrenching authentic account of Oluale Kossula who so rightly deserved to have his story told according to his recollection. Zora Neale Hurston’s coverage was remarkable in that it ensured a lasting record of those events that will impact future generations with the knowledge of our ancestors’ innate strength and perseverance.