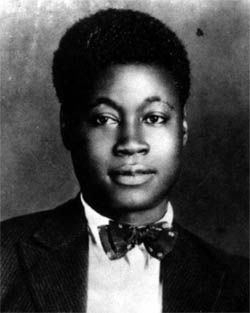

Claude McKay was a Jamaican-American poet best known for his radical sonnet “If We Must Die,” the most militant poem of the Harlem Renaissance. Mckay, a key figure of the Renaissance was recognised as the artistic counterpart to Marcus Garvey.

Festus Claudius McKay was born in Sunny Ville, Clarendon in Jamaica, on September 15, 1890. His mother and father spoke proudly of their respective Malagasy and Ashanti heritage, and infused him with racial pride and a great sense of his African heritage. Under the tutelage of his brother, schoolteacher Uriah Theophilus McKay, and a neighboring Englishman, Walter Jekyll, McKay studied poetry and philosophy. It was Jekyll, who encouraged him to write in his native Jamaican dialect, and to cease mimicking the English poets.

Festus Claudius McKay was born in Sunny Ville, Clarendon in Jamaica, on September 15, 1890. His mother and father spoke proudly of their respective Malagasy and Ashanti heritage, and infused him with racial pride and a great sense of his African heritage. Under the tutelage of his brother, schoolteacher Uriah Theophilus McKay, and a neighboring Englishman, Walter Jekyll, McKay studied poetry and philosophy. It was Jekyll, who encouraged him to write in his native Jamaican dialect, and to cease mimicking the English poets.

At age seventeen McKay departed from Sunny Ville to apprentice as a woodworker in Brown’s Town. But he studied there only briefly before leaving to work as a constable in the Jamaican capital, Kingston. In Kingston he experienced and encountered extensive racism, probably for the first time in his life. His native Sunny Ville was predominantly populated by blacks, but in substantially whyte Kingston blacks were considered inferior and capable of only menial tasks. McKay quickly grew disgusted with the city’s bigoted society, and within one year he returned home to Sunny Ville.

During his brief stays in Brown’s Town and Kingston, McKay continued writing poetry, blending his African pride with his love of English poetry. Once back in Sunny Ville, with Jekyll’s encouragement, he published his first two collections of poems, Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads. For Songs of Jamaica McKay received an award and stipend from the Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences. He used the money to finance a trip to America, and in 1912 he arrived in South Carolina. He then traveled to Alabama and enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute, where he studied for approximately two months before transferring to Kansas State College. His period in Kansas coincided with a highly-active period of the Ku Klux Klan, leading McKay to move to New York in 1914, settling in Harlem.

As in Kingston, McKay encountered racism in New York City, and that racism compelled him to continue writing poetry. McKay became active in radical politics and published his next poems in 1917 under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, in the periodical Seven Arts. His verses were discovered by critic Frank Hattis, who then included some of McKay’s other poems in Pearson’s Magazine. Among McKay’s most famous poems from this period is “To the White Fiends,” a vitriolic challenge to whyte oppressors and bigots. A few years later McKay befriended Max Eastman, communist sympathizer and editor of the magazine Liberator, which published McKay’s best-known piece of work.“If We Must Die.”

As in Kingston, McKay encountered racism in New York City, and that racism compelled him to continue writing poetry. McKay became active in radical politics and published his next poems in 1917 under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, in the periodical Seven Arts. His verses were discovered by critic Frank Hattis, who then included some of McKay’s other poems in Pearson’s Magazine. Among McKay’s most famous poems from this period is “To the White Fiends,” a vitriolic challenge to whyte oppressors and bigots. A few years later McKay befriended Max Eastman, communist sympathizer and editor of the magazine Liberator, which published McKay’s best-known piece of work.“If We Must Die.”

“If We Must Die” was written amid the violence and bloodshed that swept America during the 1919, which came to be known as “The Red Summer”. It was a period which saw a rise in race riots and hate crimes committed by whyte people against black communities. Chicago, Washington, DC, and the town of Elaine, Arkansas encountered the most violence. For example, in Chicago on July 27, 1919, a boy accidentally swam in an area of Lake Michigan that had been designated for Euro-American people only. When the boy was stoned and drowned, a fight broke out between whyte and black communities that lasted thirteen days. At the end of those thirteen days, dozens had died, over 500 people were injured, and nearly 1,000 black families had lost their homes.

With his sonnet, McKay encourages his community to take action and to fight back. The poem exploded through the American psyche, and had a powerful impact! Mckay identified Euro-Americans for what they were, a “murderous, cowardly pack” and demanded from African-Americans, courage in dealing with oppression and victimization. The sonnet was essentially a call-to-arm, advocating militant action in defending black lives and communities.

After its original publication in the July 1919 edition of the Liberator magazine, “If We Must Die” was published in political advocate Cyril Briggs’ (1888-1966) Crusader magazine, labor leader A. Philip Randolph’s Messenger magazine, and dozens more along with a string of anthologies throughout the “roaring twenties.”

McKay then left the United States for two years of European travel. He spent part of 1919 in Holland and Belgium, then moved to London and worked on the periodical Workers’ Dreadnought. In 1920 he published his third verse collection, Spring in New Hampshire, which was notable for containing “Harlem Shadows,” a poem about the plight of black prostitutes in the degrading urban environment. McKay used this poem, which symbolically presents the degradation of the entire black race, as the title for a subsequent collection.

After returning to the United States in 1921, McKay involved himself in various social and political causes. The next year he published Harlem Shadows, a collection from previous volumes and periodicals publications. This work contains many of his most acclaimed poems—including “If We Must Die”—and assured his stature as a leading member of the literary movement referred to as the Harlem Renaissance. He capitalized on his acclaim by redoubling his efforts on behalf of blacks and laborers: he became involved in the Universal Negro Improvement Association and produced several articles for its publication, Negro World, and he traveled to the Soviet Union which he had previously visited with Eastman, and attended the Communist Party’s Fourth Congress.

Eventually McKay went to Paris, where he developed a severe respiratory infection and supported himself intermittently by working as an artist’s model. His infection eventually necessitated his hospitalization, but after recovering he resumed traveling, spending what would prove to be eleven extremely productive years in Europe and North Africa; he wrote three novels—Home to Harlem, Banjo and Banana Bottom—and a short story collection during this period. Home to Harlem was the most popular of the three, though all were well received by critics. McKay’s other noteworthy fiction publication during his final years abroad was Gingertown, a collection of twelve short stories. Six of the tales are devoted to Harlem life, and they reveal McKay’s preoccupation with black exploitation and humiliation. Other tales are set in Jamaica and even in North Africa, McKay’s last foreign home before he returned to the United States in the mid-1930s.

Returning to Harlem, McKay began work on an autobiography entitled A Long Way from Home, which focuses on his experiences of oppression as a black individual in a whyte society.

McKay went through several changes toward the end of his life. He embraced Catholicism, retreating from Communism entirely, and officially became an American citizen in 1940. His experiences working with Catholic relief organizations in New York inspired a new essay collection, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, which offers observations and analysis of the African-American community in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s.

McKay eventually moved to Chicago and worked as a teacher for a Catholic organization. By the mid-1940s his health had deteriorated. He endured several illnesses throughout his last years and eventually died of heart failure on May 22, 1948.

Many years after his death, McKay continues to be admired for his intense commitment to expressing the predicament of Black people and for devoting his art and life to social protest.

In 2012, a researcher discovered an unpublished Claude McKay novel, Amiable with Big Teeth, in the Columbia University archives.

Source:

http://www.shmoop.com/if-we-must-die/

http://www.biography.com/people/claude-mckay-9392654#literary-career

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/claude-mckay