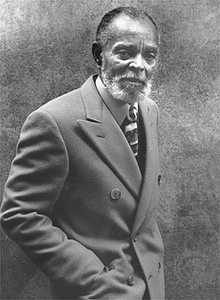

Chester Himes was an African American writer best known for his series of Harlem detective novels. In 1958 he won France’s Grand Prix de Littérature Policière. In his lifetime he published 17 novels, more than 60 short stories, and 2 volumes of autobiography in which he detailed the pain of being an African American writer in the twentieth century.

Named for his maternal grandfather, Chester Bomar Himes, was born on July 29, 1909, in Jefferson City, Missouri, the youngest son of Joseph Sandy and Estelle Bomar Himes. His father was a professor of metal trades at Lincoln Institute, while his “genteel, churchgoing, cultured, prideful, proper, driven, ambitious” mother, taught at the elite Scotia Seminary in North Carolina before her marriage. His parents’ marriage was unhappy and eventually ended in divorce.

Named for his maternal grandfather, Chester Bomar Himes, was born on July 29, 1909, in Jefferson City, Missouri, the youngest son of Joseph Sandy and Estelle Bomar Himes. His father was a professor of metal trades at Lincoln Institute, while his “genteel, churchgoing, cultured, prideful, proper, driven, ambitious” mother, taught at the elite Scotia Seminary in North Carolina before her marriage. His parents’ marriage was unhappy and eventually ended in divorce.

When Himes was about 12 years old, his father took a teaching job in the Arkansas Delta at Branch Normal College, and soon a tragedy took place that would profoundly shape Himes’s view of race relations. He had misbehaved and his mother made him sit out a gunpowder demonstration that he and his brother, Joseph Jr., were supposed to conduct during a school assembly. Working alone, Joseph mixed the chemicals; they exploded in his face. Rushed to the nearest hospital, the blinded boy was refused treatment because of Jim Crow laws. “That one moment in my life hurt me as much as all the others put together,” Himes wrote in The Quality of Hurt.

“I loved my brother. I had never been separated from him and that moment was shocking, shattering, and terrifying….We pulled into the emergency entrance of a white people’s hospital. White clad doctors and attendants appeared. I remember sitting in the back seat with Joe watching the pantomime being enacted in the car’s bright lights. A white man was refusing; my father was pleading. Dejectedly my father turned away; he was crying like a baby. My mother was fumbling in her handbag for a handkerchief; I hoped it was for a pistol.”

Himes family left Pine Bluff and relocated to Cleveland Ohio where he attended East High School. He planned on attending Ohio State University, and in order to earn money he worked as a busboy at the Wade Park Manor Hotel. While on the job Himes was seriously injured after he fell down an elevator shaft. The hotel was found liable and Himes was awarded a monthly disability payment. He enrolled at Ohio State but was expelled for playing a prank; after he led a group of what he called ”proper young black” students from a formal fraternity dance to a slum brothel.

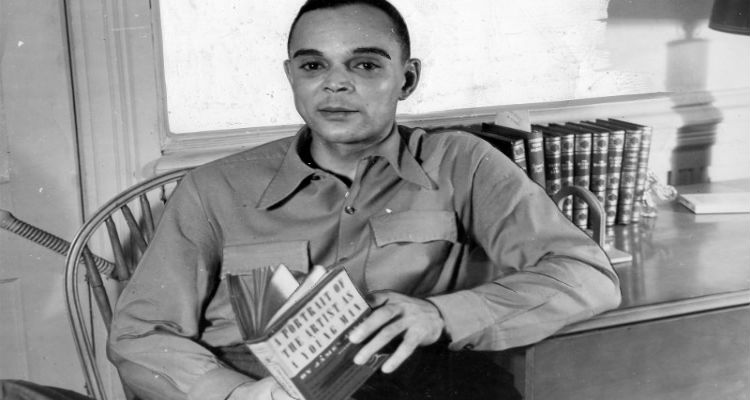

Dismissed from Ohio, Himes became increasingly involved in crime. After several arrests for burglary, when he was 19, Himes was chained upside down, beaten by police until he confessed to an armed robbery. He was sentenced for twenty to twenty-five years hard labor, and incarcerated in the Ohio State Penitentiary. At the prison a fire killed 300 inmates. In the smoldering ashes, Himes, inspired by the Black Mask writings of Dashiell Hammett and by the grim events he’d witnessed, bought himself a Remington typewriter and began writing short stories and had them published first in black newspapers and magazines, then, in 1934, in Esquire, initially under the byline of his prison number, 59623. Himes wrote, “I grew to manhood in the Ohio State Penitentiary. I was nineteen years old when I went in and twenty-six years old when I came out. I became a man dependent on no one but myself. I learned all the behavior patterns necessary for survival… I survived, I suppose, because I knew how to gamble.” By the time he was paroled in 1936, he had become a nationally-known writer.”

Shortly after his parole, Himes completed a novel based on his prison experience originally titled Black Sheep. He had difficulty finding a pulisher, and experienced rejection year after year. In 1950, Henry Holt verbally accepted the book, but when Himes showed up to sign the contract he was told that the acceptance had been overruled from higher up. By the time the novel was accepted in 1952–sixteen years after he left prison–Himes would have published two of his five protest novels: If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945) and Lonely Crusade (1947). The prison novel meanwhile had gone through many rewrites with ever-changing titles. When at last published by Coward-McCann in 1952 under the new title Cast the First Stone, the novel was radically different from any of Himes’ manuscripts.

Other protest novels include The Third Generation (1954) and The Primitive (1955). In these works, Himes depicts the destruction of interracial relationships through race and gender stereotype. Their protagonists struggle unsuccessfully with environmental and social forces that shape their violent destinies.

In 1937 Himes went to work for the Works Project Administration (WPA), at first as a laborer and then a research assistant for the Cleveland Public Library. On August 13, 1937, he married Jean Lucinda Johnson, whom he had lived with before his incarceration. By 1938 Himes was working for the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project, assigned to write a history of the state of Ohio and later a guide to Cleveland. In retrospect Himes considered this one of the happier periods in his life, both personally and professionally. Himes was even writing a column (though unsigned) for the Cleveland Daily News titled, “This Cleveland.”

When WWII began, he moved to Los Angeles and had a brief career as a screenwriter, for Warner Brothers, which was terminated when Jack L. Warner heard about him and said “I don’t want no niggers on this lot.” Himes later wrote in his autobiography:

“Up to the age of thirty-one I had been hurt emotionally, spiritually and physically as much as thirty-one years can bear. I had lived in the South, I had fallen down an elevator shaft, I had been kicked out of college, I had served seven and one half years in prison, I had survived the humiliating last five years of Depression in Cleveland; and still I was entire, complete, functional; my mind was sharp, my reflexes were good, and I was not bitter. But under the mental corrosion of race prejudice in Los Angeles I became bitter and saturated with hate.”

However, during this time, he published stories and essays in such black-run magazines as Crisis and Opportunity. By 1944 Himes was working on If He Hollers Let Him Go, a semi-autobiographical tale of the absurd and rage-filled life of a young, educated African American man who eventually lands a job in the shipyards. He was awarded a Rosewald fellowship to complete it. That year he moved to New York City. After the novel’s publication Himes returned to California and began working on his second novel Lonely Crusade. The following year Himes spent two months at the famed Yaddo Writer’s Colony in Saratoga Springs, New York. It seemed his career was finally on its way. However his home life suffered and by 1950 Himes and his wife had separated for good.

In the mid-1950s Himes decided to settle in France permanently, already the refuge for such prominent African American writers as Richard Wright and James Baldwin. In 1957, Marcel Duhamel, publisher of the detective story series “La Serie Noire,” convinced him to write serial detective fictions. Over the next twelve years Himes wrote a series of novels set in New York City’s Harlem, featuring the African American detectives, Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones. The series became known as the “Harlem Cycle.” The first of these works, For Love of Imabelle (1957; revised as A Rage in Harlem in 1965), received the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 1958.

Other novels include The Crazy Kill (1959), Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965), and Blind Man with a Pistol (1969; later retitled Hot Day, Hot Night). Among his other works of this period are Run Man, Run (1966), a thriller; Pinktoes (1961), a satirical work of interracial erotica; and Black on Black (1973), a collection of stories.

Cotton Comes to Harlem, the best-known novel in the “Harlem Cycle,” was made into a 1970 film directed by Ossie Davis and starring Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques.

In the early 1960s Himes traveled widely around Europe and back and forth to the United States. He also became more deeply involved with Lesley Packard, a journalist, whom he married in 1965.

In 1969 Himes moved to Moraira, Spain, where he died in 1984 from Parkinson’s Disease. He is buried at Benissa cemetery.

In addition to his novels, Himes published two autobiographical volumes: The Quality of Hurt (1972) and My Life of Absurdity (1976). The novel, Plan B, which was unfinished when he died, was published posthumously in 1993.

Bibliography

Novels and stories

If He Hollers Let Him Go, 1945

Lonely Crusade, 1947

Cast the First Stone, 1952

The Third Generation, 1954

The End of a Primitive, 1955

For Love of Imabelle, (1957; revised as A Rage in Harlem, 1965)

The Real Cool Killers, 1959

The Crazy Kill, 1959

The Big Gold Dream, 1960

All Shot Up, 1960

Run Man Run, 1960

Pinktoes, 1961

Cotton Comes to Harlem, 1965

The Heat’s On, 1966

Blind Man with a Pistol, 1969

Black on Black, 1973

A Case of Rape, 1980

The Collected Stories of Chester Himes, 1990

Plan B, 1993

Yesterday Will Make You Cry, 1998

Autobiography

The Quality of Hurt (1973)

My Life of Absurdity (1976)

Source:

http://www.math.buffalo.edu/~sww/HIMES/himes-chester_BIO.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester_Himes

https://www.nytimes.com/books/01/03/18/reviews/010318.18politot.html

http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~hbf/himes.html

http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/DocumentToolsPortletWindow?displayGroupName=Reference&jsid=2edacd48b0bbe88b9eca498d64189e23&action=2&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK1631007975&u=bccc_main&zid=5e4e72aa2b3987ab1bcee13ffb0d10f6

1 comment

Chester Himes, what an awesome journey. He took each step to get to where he vision himself. He never gave up. A lesson in itself. Many leaves fell from the tree, but the tree grew strong.