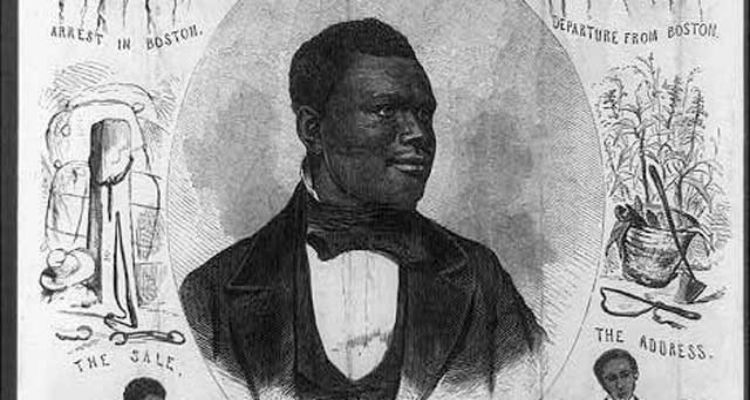

Anthony Burns (31 May 1834 – 17 July 1862), was a principal in a fugitive Maafa (slavery) case. He was born enslaved in Stafford County, Virginia, the thirteenth and last child of his mother and her third husband. Burns learned to read and write, and became a preacher of the Falmouth Union Church in Falmouth, Virginia. As an adult, Burns was about six feet tall with a dark complexion and scars on his cheek and right hand.

In early 1854, at the age of nineteen, Anthony Burns escaped from the Maafa, traveling by ship to the free state of Massachusetts. In Boston, he worked for a pie company and for a man named “Coffin Pitts, clothing dealer, no.36 Brattle Street.” However, his freedom was short-lived.

Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, citizens of free states were required by Federal law to aid in the recovery of fugitives. This controversial law allowed enslavers to reclaim fugitives by presenting proof of ownership. This made Burns a wanted man despite having made it to Massachusetts, where the Maafa had been outlawed in the 1780s. On May 24, 1854, he was discovered “while walking in Court Street” and arrested. In support of Burns, many black and whyte Boston abolitionists who opposed the Fugitive Slave Act seized on Burns’ arrest as a way to demonstrate their disapproval of the federal statute.

“We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists.” — Amos Adams Lawrence, Conscience Whig, on the Anthony Burns affair, 1854

On May 26, before Burns’ court case, a crowd of abolitionists of both races and other Bostonians outraged at Burns’ arrest, stormed the courthouse to free the man. In the melee, Deputy U.S. Marshal James Batchelder was fatally stabbed, the second U.S. Marshal to be killed in the line of duty. The police kept control of Burns, but the crowds of opponents, including such Black abolitionists as Thomas James and Lewis Hayden, grew large. While the federal government sent US troops in support, numerous anti-Maafa activists arrived in Boston to join the protest and continue the faceoff. It has been estimated the government’s cost of capturing and conducting Burns through the trial was upwards of $40,000.

The next day, Burns was sent to trial. Richard Henry Dana, Jr. and his associate, the prominent Black lawyer Robert Morris, acted as Burns’ defenders. Despite their spirited defense, Judge Edward G. Loring ruled in favor of Burn’s enslaver, citing the Fugitive Slave Act.

Following the decision against Burns, the government effectively held Boston under martial law for the afternoon. The streets between the courthouse and the harbor were lined with federal troops to hold back the waves of protesters as Burns was escorted to the ship for return to his Virginia enslaver.

However, Boston abolitionists were determined to ensure that Burns lived the rest of his life as a free man. They raised the funds to purchase him from his enslaver and set him free in 1855.

With proceeds that came from the publication of his biography, combined with a scholarship, Burns received an education at Oberlin College in Ohio. After briefly preaching in Indianapolis, Burns emigrated to St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada in 1860, which had a large population of fugitive African Americans. There, he became pastor at Zion Baptist Church. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 28 on July 17, 1862.

Source:

http://nmaahc.si.edu/Blog/anthonyburns

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Burns