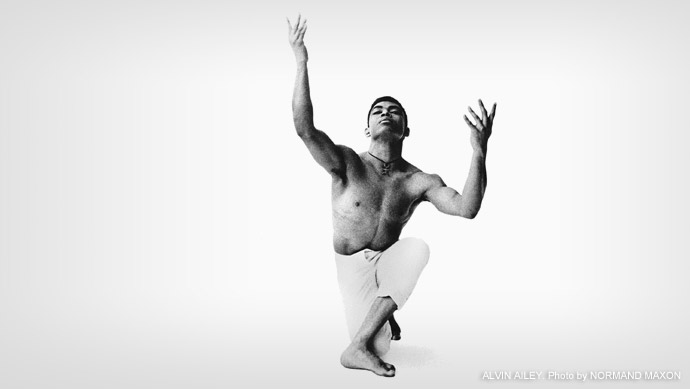

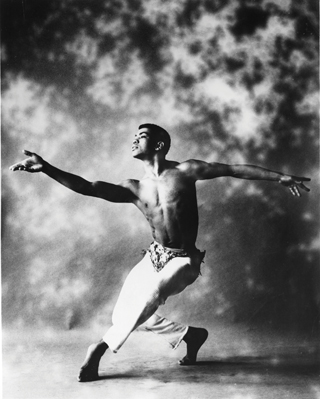

Alvin Ailey Jr., the African American choreographer, dancer and activist is credited with popularizing modern dance and revolutionizing African-American participation in 20th-century concert dance. His company, The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, became known as the “Cultural Ambassador to the World” because of its extensive international touring.

Ailey was born to Alvin and Lula Elizabeth Ailey on January 5, 1931, in Rogers, Texas. He was an only child, and his father, a laborer, left the family when Alvin Jr. was less than one year old. At the age of six, Alvin Jr. moved with his mother to Navasota, Texas. As he recalled in an interview in the New York Daily News Magazine, “There was the white school up on the hill, and the black Baptist church, and the segregated [only members of one race allowed] theaters and neighborhoods. Like most of my generation, I grew up feeling like an outsider, like someone who didn’t matter.”

In 1942 Ailey and his mother moved to Los Angeles, California, where his mother found work in an aircraft factory. Ailey became interested in athletics and joined his high school gymnastics team and played football. An admirer of dancers Gene Kelly (1912–1996) and Fred Astaire (1899–1987), he also took tap dancing lessons at a neighbor’s home. His interest in dance grew when a friend took him to visit the modern dance school run by Lester Horton, whose dance company (a group of dancers who perform together) was the first in America to admit members of all races. Unsure of what opportunities would be available for him as a dancer, however, Ailey left Horton’s school after one month. After graduating from high school in 1948, Ailey considered becoming a teacher. He entered the University of California in Los Angeles to study languages. When Horton offered him a scholarship in 1949 Ailey returned to the dance school. He left again after one year, however, this time to attend San Francisco State College.

For a time Ailey danced in a nightclub in San Francisco, California, then he returned to the Horton school to finish his training. When Horton took the company east for a performance in New York City in 1953, Ailey was with him. When Horton died suddenly, the young Ailey took charge as the company’s artistic director. Following Horton’s style, Ailey choreographed two pieces that were presented at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Massachusetts. After the works received poor reviews from the festival manager, the troupe broke up.

Despite the setback, Ailey’s career stayed on track. A Broadway producer invited him to dance in House of Flowers, a musical based on Truman Capote’s (1924–1984) book. Ailey continued taking dance classes while performing in the show. He also studied ballet and acting. From the mid-1950s through the early 1960s Ailey appeared in many musical productions on and off Broadway, among them: The Carefree Tree; Sing, Man, Sing; Jamaica; and Call Me By My Rightful Name. He also played a major part in the play Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright.

In 1958, he founded Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater to carry out his vision of a company dedicated to enriching the American modern dance heritage and preserving the uniqueness of the African-American cultural experience.

In the 1960s, Ailey took his company on the road. The U.S. State Department sponsored his tour, which helped create his international reputation. He stopped performing in the mid-1960s, but he continued to choreograph numerous masterpieces. Ailey’s Masakela Language, which probed the experience being black in South Africa, premiered in 1969. He also formed the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center—now called the Ailey School—that same year.

He established the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center (now The Ailey School) in 1969 and formed the Alvin Ailey Repertory Ensemble (now Ailey II) in 1974. Mr. Ailey was a pioneer of programs promoting arts in education, particularly those benefiting underserved communities.

Also in 1974, Ailey used the music of Duke Ellington as the backdrop for Night Creature. He also expanded his dance company by establishing the Alvin Ailey Repertory Ensemble that same year. During his long career, Ailey choreographed close to 80 ballets.

By the late 1970s Ailey’s company was one of America’s most popular dance troupes. Its members continued touring around the world, with U.S. State Department backing. They were the first modern dancers to visit the former Soviet Union since the 1920s. In 1971 Ailey’s company was asked to return to the City Center Theater in New York City after a performance featured Ailey’s celebrated solo, Cry. Danced by Judith Jamison, she made it one of the troupe’s best known pieces.

Dedicated to “all black women everywhere—especially our mothers,” the piece depicts the struggles of different generations of black American women. It begins with the unwrapping of a long white scarf that becomes many things during the course of the dance, and ends with an expression of belief and happiness danced to the late 1960s song, “Right On, Be Free.” Of this and of all his works Ailey told John Gruen in The Private World of Ballet, “I am trying to express something that I feel about people, life, the human spirit, the beauty of things.…”

Ailey suffered a breakdown in 1980 that put him in the hospital for several weeks. At the time he had lost a close friend, was going through a midlife crisis, and was experiencing money problems. Still, he continued to work, and his reputation as a founding father of modern dance grew during the decade.

Ailey received many honors for his choreography, including a Dance magazine award in 1975; the Springarn Medal, given to him by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1979; and the Capezio Award that same year. In 1988 he was awarded the Kennedy Center Honors prize. Ailey died of a blood disorder on December 1, 1989. Thousands of people flocked to the memorial service held for him at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Sources:

http://www.alvinailey.org/about/people

http://www.notablebiographies.com/A-An/Ailey-Alvin.html#ixzz3wKCNQEmG

http://www.biography.com/people/alvin-ailey-9177959#career-highlights

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alvin_Ailey