On April 14, 1816, the largest Maafa (Atlantic slavery) revolution in the history of Barbados, broke out. Now known as Bussa’s Rebellion, the uprising lasted over two days before it was suppressed by the British military forces and the island’s militia. Martial law was declared on 15 April, and over a seven week period a courts-martial tried a number of the uprising’s alleged leaders. Ultimately four free people were executed for their participation, over 1000 enslaved people lost their lives, either killed in battle or executed as a result of courts martial, and in January 1817, 124 “convicts and other dangerous persons concerned in the late insurrection” were transported out of Barbados. The uprising surprised the slavocracy community who believed that the people in bondage on the island were well treated and enjoyed a level of freedom not had in other territories. One enslaver later recollected how, “the night of the insurrection I would and did sleep with my chamber door open, and if I had possessed ten thousand pounds in my house I should not have had any more precaution, so well convinced I was of their attachment.”

Bussa, now a national hero of Barbados, was the principal leader of the uprising, although there were also several persons (enslaved and free) who had leadership roles. Each plantation actively involved in the uprising had a leader. Two crucial plantations were Simmons Plantation, lead by John and Nanny Grigg and mostly importantly Jackey; as well as Bailey plantation, lead by King Wiltshire, Dick Bailey, Johnny and Bussa after whom the uprising was named. The leadership also included several free Black people, among them Cain Davis, John Richard Sarjeant, a man named Roach, and Joseph Pitt Washington Franklin, who was executed on the morning of 2 July 1816. Franklin, it seems, had planned the outbreak, but it was Bussa who was the leader of the war for freedom. Bussa was given the military title and rank of General by the people.

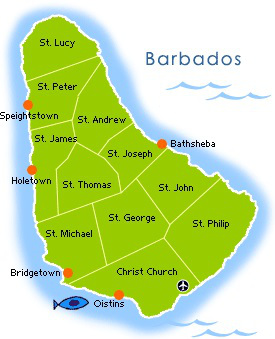

General Bussa was an African driver at the Bailey Plantation at St. Phillip. He was respected by both bondspeople and enslavers alike. He is believed to be the only African in his position as 92% of the bondspeople on Barbados were island-born. General Bussa commanded a total of 400 enslaved men and women to fight against their oppressors.

In the planning and organization of the uprising, a campaign was undertaken by three free Black men who were literate; Cain Davis, Roach, and Richard Sarjeant. Davis held meetings with bondspeople from several different plantations, informing them of the emancipation rumours. Sarjeant also mobilize bondspeople in the central parishes. The final day of planning took place at the River plantation on Good Friday night April 12. It was disguised by the cover of a dance, and leaders such as Bussa, Jackey, and Davis were present.

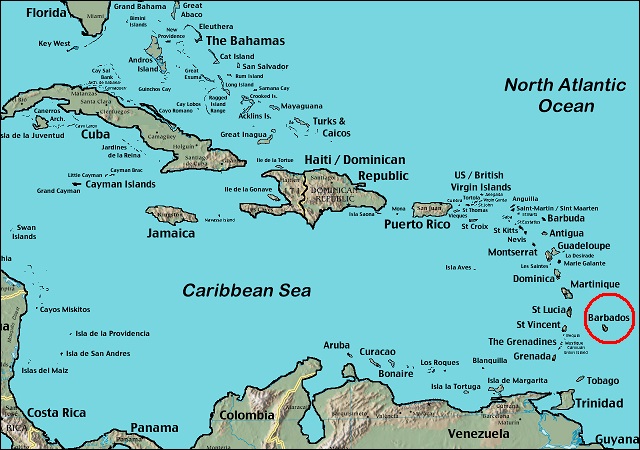

The uprising was to begin on Easter Monday and from there the start of arsonist attack upon the slavocracy community. That was not the case as the uprising broke out earlier than originally planned believed to be the result of drunken bondsman relaying erroneous information to the freedom fighters. Therefore, the uprising started Easter Sunday night on April 14. It broke out with cane fields being burnt in St Phillip, signaling prematurely to freedom fighters in central and southern parishes that the uprising had begun. By the early hours of the morning, seventy of the largest plantations were aflame and the uprising had spread across to neighbouring parishes. The slavocracy community fled to Bridgetown, the colonial capital, in panic. Despite the scope of the uprising, there was no great massacre done by the freedom fighters; and only two Europeans were killed. However, approximately 25% of the years sugar crop was burnt and property damage was estimated at £175,000.

Martial law was immediately declared on April 15, 1816; and the uprising was put down by the militia and the imperial troops (which included enslaved soldiers) in three days and effectively over within a week. In addition, Barbados’ topography made it quite easy to put the insurrection down as the land was mainly flat.

The governor of Barbados, James Leith, reported that by September, five months after the uprising had ended, 144 people had been executed, 70 people were later sentenced to death, while 170 were deported to neighboring British colonies in the Caribbean. Alleged freedom fighters were also subject to public floggings and executions during the entire eighty days of martial law.

Those who were captured were torture and thus ended up incriminating others which led to further captures. For example, five enslaved men are known to have given testimonies which were featured in the published investigation of the uprising that was conducted by a committee of the Barbados House of

Assembly: Daniel, King Wiltshire, Cuffee Ned, Robert, and James Bowland. Only three mentioned Bussa in their “examinations”. In his “examination” Daniel, a carpenter at The River plantation in St. Philip first implicates two free people (Cain Davis and John Richard Sarjeant) as leading conspirators. He mentions that about three weeks before the uprising he heard these men claim that the British government was to free the bondspeople, but they were not free-and-“-they must fight-for it.” Daniel also saw Bussa who attended a dance at The River on Good Friday night, speaking with Davis and Sarjeant.

Also, in his “confession” at the court-martial, Robert, a bondsman at Simmons in St.Philip, implicates several bondspeople as leaders of the uprising, including Nanny Grigg, and Jackey, the driver at Simmons who Robert accuses of being “one of the head men of the insurrection.”

Finally, in his “confession” James Bowland, a bondsman at The River plantation mentions Bussa in the following sentence: “That Bussoe, the ranger; King Wiltshire, the carpenter; Dick Bailey, the mason; Johnny, the standard bearer; and Johnny Cooper, a cooper; were the principal instigators of the insurrection at Bailey’s.”

Although the uprising was unsuccessful in ridding Barbados of the “robbers of men” and only lasted a few days, it is believed that the freedom fighters would have known that it would have been difficult for them to win but they were willing to sacrifice their lives. Hence, the uprising is seen “as a shining example of defiance and resistance, emerging from the rubble of a history of enslavement.”

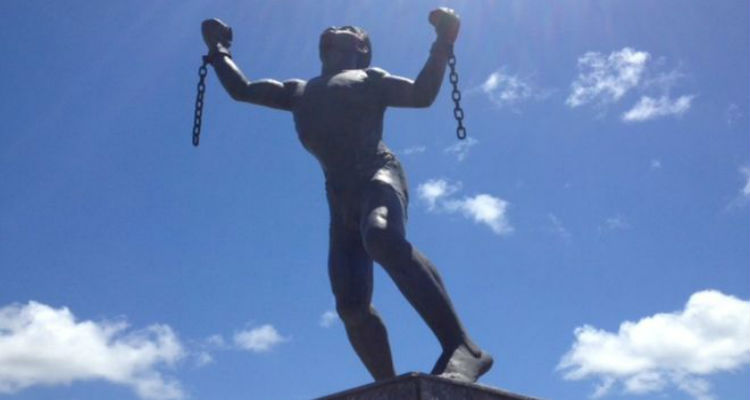

In 1985, the Barbados government unveiled the Emancipation Statue, created by Karl Broodhagen, in Haggatt Hall, in the parish of St Michael. It depicts an enslaved man triumphantly raising his arms, broken shackles dangling from his wrists, with his fists clenched, looking up to the sky in a kind of reverent victory. The statue eventually became commonly known as “Bussa” by the local people.

In 1998, the Parliament named Bussa as one of the ten National Heroes of Barbados.

Source:

http://www.nlj.gov.jm/history-notes/The%20Emancipation%20Wars.pdf

http://jeromehandler.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/1816-Revolt-2000.pdf

https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/31536/McNaughtL_TPC.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y