Ona Judge, known as Oney Judge Staines after marriage, was a bondwoman who worked on George Washington’s Mount Vernon labor camp/plantation, in Virginia. Beginning in 1789, she worked as a lady’s maid to First Lady Martha Washington in the presidential households in New York City and Philadelphia. In 1796, with the aid of Philadelphia’s free African-American community, she escaped from the President’s mansion in Philadelphia. Ona relocated to New Hampshire, where she lived for the rest of her life. Much is known of her life in comparison to other bondpeople at Mount Vernon because she was interviewed by abolitionist newspapers in 1845 and 1847.

A silhouette of Ona Judge from Lives Bound Together, Mount Vernon.

Ona Judge was born at Mount Vernon around 1773, the daughter of a bondwoman, Betty, who was a seamstress. Her father, Andrew Judge, was a English tailor who was an indentured servant at Mount Vernon in the early 1770s. Through her mother, she had four half siblings: Austin, whose father is unknown; Tom Davis and Betty Davis, the children of an indentured weaver named Thomas Davis; and Philadelphia (later Philadelphia Costin). Like her mother, Ona was a skilled seamstress although she never knew how to read or write. When she was ten-years old, Ona began working in the mansion.

On February 4, 1789, George Washington was elected president, and in April he left for New York, the federal capital. It is said that Ona was a personal favorite of her enslavress, Martha, and therefore, she was one of the bondpeople brought to New York City in 1789 by the Washingtons to work in the presidential residence, and then to Philadelphia in 1790 with the change in the capital. Ona is recorded as accompanying Martha on shopping trips and social visits. There are entries in the household ledgerbooks for clothes for the teen-aged girl and trips to the circus. However, Ona was never kept in Pennsylvania for more than six months at a time because Washington was aware of the Pennsylvania law passed in 1780 – “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” – which required that any enslaved person living in Pennsylvania for six uninterrupted months be freed.

In a letter to his personal secretary, dated April 12, 1791, Washington ordered that his bondpeople be sent back to Virginia before their six months expired in May, and then returned to Philadelphia. He worried that should his bondpeople learn of the law they might be tempted by freedom. He also noted that all but two of his bondpeople in Philadelphia, including Judge and Austin, were enslaved “dower” persons , meaning that they had come to the marriage with his wife and were technically enslaved by the estate of her first husband. Should he lose them, Washington wrote, he would be forced to reimburse the Custis estate.

On May 21, 1796, while the household was preparing to retreat to Mount Vernon for the summer, Ona simply walked out of the mansion while her enslavers were eating dinner. She was hidden by her friends until she could find passage on a northbound ship, the Nancy, a sloop captained by John Bowles and bound for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In order to keep Bowles’ involvement from anyone who could condemn him, Ona kept the identity of the ship’s captain, a secret for years. “I never told his name till after he died, a few years since, lest they should punish him for bringing me away,” she said.

Ona had learned that she would be given to Martha’s eldest granddaughter who had married an English expatriate. The Washingtons had invited the couple to visit Philadelphia to stay at the President’s House. Martha informed Ona that she was to be given as a gift to the bride, perhaps after the Washingtons’ death. Ona later told a reporter that she was “determined” never to be the bondperson of Elizabeth Custis Law.

Therefore: “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty,” she said in an 1845 interview. “I had friends among the colored people of Philadelphia, had my things carried there beforehand, and left Washington’s house while they were eating dinner.”

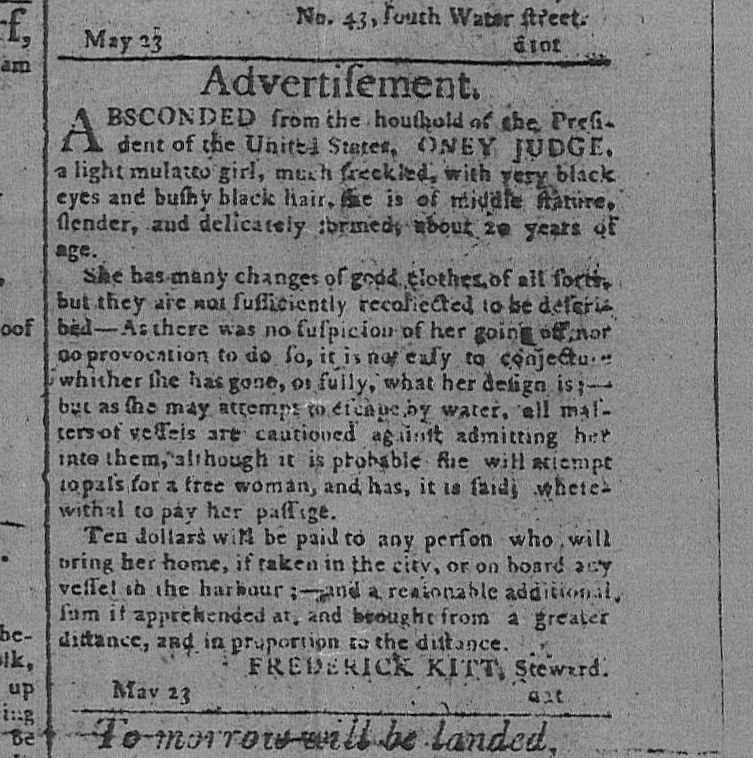

When Martha learned of Ona’s self-emancipation, she felt betrayed and claimed that Ona must have been abducted and seduced by a Frenchman. She wrote that Ona had always been well-treated, and even had a room of her own. The First Lady urged the President to advertise a reward for Ona’s recapture. Notices offering a $10 reward for her return appeared on May 24 in the Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Daily Advertiser and, a day later, in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser.

Runaway Advertisement for Oney Judge in The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 24 May 1796

In the advertisement, Ona was described as “a light [mixed-race] girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair, she is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed.” The ad also noted that Ona has “many changes of good clothes, of all sorts.”

A newspaper report from 1845 noted that her name at the time of her self-emancipation had been Ona Maria Judge. Oney is a nickname that appears in Washington’s papers and in advertisements for her return.

Ona was first sighted in New York, and when it was reported to the Washingtons that she was seen walking on a street in Portsmouth, her enslavers made attempts to re-enslave her.

Washington asked Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott to handle the matter, and the latter wrote to Joseph Whipple, the Collector of Customs of Portsmouth, requesting his help in the return of the President’s wife’s property. Whipple succeeded in interviewing Ona on the ruse that he was interested in hiring her as a maid. He even arranged for her to travel to Virginia, but she failed to appear at the designated time. He reported to Wolcott that abducting Ona and placing her on a ship headed south might cause a riot on the docks, and that, “After a cautious examination it appeared to me that she had not been decoyed away [by a Frenchman] as had been apprehended, but that thirst for [complete] freedom which she was informed would take place on her arrival here and Boston had been her only motive for absconding.”

Ona tried to negotiate through Whipple. She offered to return to the Washingtons, but only if she would be guaranteed freedom upon their deaths. Washington was offended by Ona’s refusal and request and responded in person to Whipple’s letter: “To enter into such a compromise with her, as she suggested to you, is totally inadmissible [sic], it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference [of freedom], and thereby discontent beforehand the minds of all her fellow-servants who by their steady attachments are far more deserving than herself of favor.”

In another attempt, Washington wrote to his wife’s nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., who was then serving in the Senate of Virginia, requesting that he travel to New Hampshire to persuade Ona, by force if necessary, to return to Mount Vernon with her infant child. However, Ona had allies in Portsmouth, who alerted her to Bassett’s arrival, as well as his intentions.

On January 8, 1797, Ona married the free African-American sailor John Staines and the couple had three children before his death in 1803. After her husband’s death, the family became impoverished and had to move in with the Jacks, a free African-American family in Greenland. In August 1816, Ona sent her daughters to work as indentured servants with a neighbor. Her son became a sailor. All three children were dead by 1845.

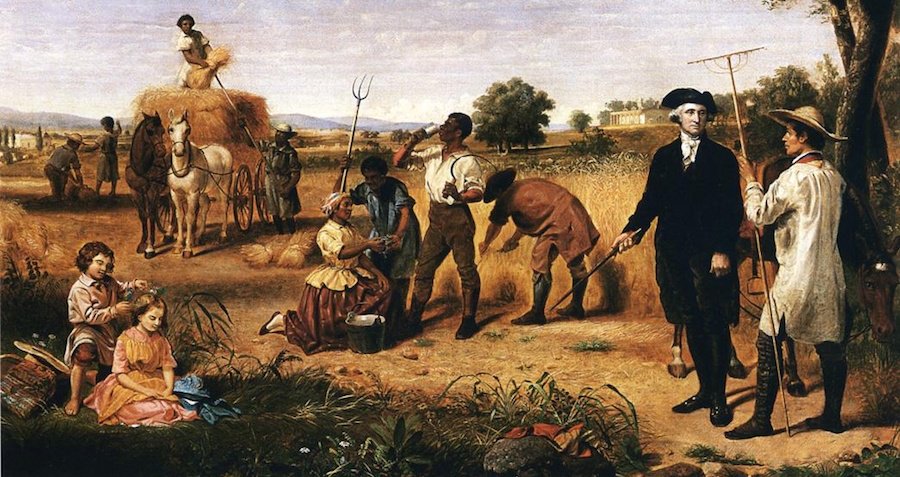

Washington as a Farmer at Mount Vernon, depicting him with his bondpeople, by Junius Brutus Stearns (1851).

Ona would later give a series of interviews to abolitionist newspapers alleging that the Washingtons administered brutal punishments to rebellious bondpeople, and tried to circumvent Pennsylvania’s 1780 gradual abolition law by moving bondpeople to and from the state every six months.

In her first newspaper interview, printed in The Granite Freeman of Concord, New Hampshire on May 22, 1845, Ona was asked if she regretted her escape, “as she had labored so much harder since than before.” She replied, “No, I am free, and have, I trust been made a child of God by the means.”

Ona “Oney”Judge Staines died at age seventy-five, on February 25, 1848 in Greenland, New Hampshire.

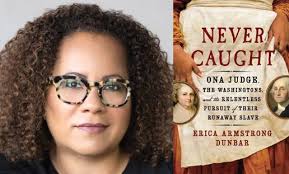

The story of Ona’s escape and life on the run in New Hampshire is the subject of Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge.

Time Line

ca. 1773 – Ona Judge is born enslaved at Mount Vernon, the daughter of Betty, a seamstress, and probably the English tailor Andrew Judge, an indentured servant.

March 1, 1780 – The Pennsylvania legislature passes “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.”

ca. 1783 – Ona Judge becomes the lady maid of Martha Washington at Mount Vernon.

March 29, 1788 – The Pennsylvania legislature passes “An Act to Explain and Amend an Act Entitled ‘An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.'”

February 4, 1789 – George Washington is unanimously elected the first U.S. president by electors chosen by votes of individual state assemblies.

April 16, 1789 – George Washington, just elected U.S. president, leaves Mount Vernon for the capital, New York City.

May 16, 1789 – Martha Custis Washington and her household leave Mount Vernon to join George Washington in New York City.

May 27, 1789 – President George Washington meets his wife and family in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. They have just arrived from Mount Vernon.

August 30, 1790 – President George Washington and his family leave New York City and return to Mount Vernon for an extended visit.

November 1790 – President George Washington and his family move to Philadelphia, site of the new federal capital.

April 5, 1791 – In a letter to George Washington, Tobias Lear informs the president of a Pennsylvania law that complicates his holding of bondpeople in the federal capital.

April 12, 1791 – In a letter to Tobias Lear, George Washington asks his secretary to temporarily relocate his bondpeople from Philadelphia to Mount Vernon.

March 21, 1796 – Elizabeth Parke Custis and Thomas Law, an Englishman twenty years her senior, marry at Hope Park, in Fairfax County.

May 21, 1796 – Ona Judge, the enslaved lady maid to Martha Custis Washington, escapes from the President’s House in Philadelphia while the family is eating dinner.

May 24, 1796 – An advertisement seeking the capture of Oney Judge is published in the Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Daily Advertiser.

May 25, 1796 – An advertisement seeking the capture of Oney Judge is published in Claypool’s American Daily Advertiser.

June 28, 1796 – Thomas Lee writes George Washington that the fugitive bondwoman Oney Judge has been sighted in New York City.

September 1, 1796 – George Washington writes to Oliver Wolcott Jr. about Oney Judge.

October 4, 1796 – In a letter to Oliver Wolcott Jr., Joseph Whipple writes about his meeting with the Oney Judge.

November 28, 1796 – In a letter to Joseph Whipple, George Washington articulates the terms on which Oney Judge may return.

December 22, 1796 – In a letter to George Washington, Joseph Whipple promises to do his best to capture the Oney Judge.

January 8, 1797 – John Staines and Oney Judge marry in Greenland, New Hampshire. They will have three children.

August 11, 1799 – In a letter to Burwell Bassett, George Washington requests his help in capturing the Oney Judge.

December 14, 1799 – George Washington dies at Mount Vernon after a short illness.

May 3, 1803 – The death of John Staines, the husband of Oney Judge, is announced in the New-Hampshire Gazette.

August 1816 – Oney Judge Staines sends her daughters to labor as indentured servants with a neighbor.

May 22, 1845 – An interview with Oney Judge is published in the Granite Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper in Concord, New Hampshire.

January 1, 1847 – An interview with Judge appears in the Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper in Boston.

February 25, 1848 – Oney Judge Staines dies in Greenland, New Hampshire.

Source:

Wolfe, B. Oney Judge (ca. 1773–1848). (2017, April 19). In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Judge_Oney_ca_1773-1848.

https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/ona-judge-the-slave-who-ran-away-from-george-washington/

https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/ona-judge

http://www.ushistory.org/presidentshouse/slaves/oney.php

Ona Judge, The Story Of The Slave Who Escaped Washington’s Plantation