“It is my thought that clean living and a strict observance of the golden rule of true sportsmanship are foundation stones without which a championship structure cannot be built.”

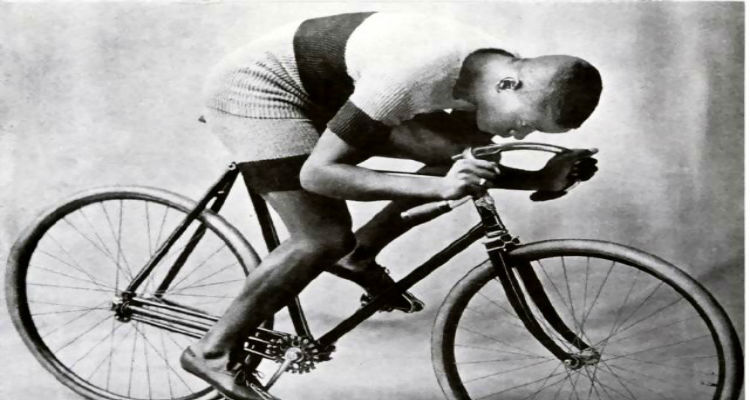

Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor was the first African-American world champion cyclist and only the second Black man to win a world championship in any sport — after Canadian boxer George Dixon. Nicknamed “the Black Cyclone,” Taylor won the world 1 mile (1.6 km) track cycling championship in 1899, and by 1900, he held several major world records and had competed in events around the globe.

“At the dawn of the 20th century, cycling was the most popular sport in both America and Europe, with tens of thousands of spectators drawn to arenas and velodromes to see highly dangerous and even deadly affairs that bore little semblance to bicycle racing today. In brutal six-day races of endurance, well-paid competitors often turned to cocaine, strychnine and nitroglycerine for stimulation and suffered from sleep deprivation, delusions and hallucinations along with falls from their bicycles… One of the first sports superstars… Marshall W. Taylor was just a teenager when he turned professional and began winning races on the world stage, and President Theodore Roosevelt became one of his greatest admirers. But it was not Taylor’s youth that cycling fans first noticed when he edged his wheels to the starting line. Nicknamed “the Black Cyclone,” he would burst to fame as the world champion of his sport almost a decade before the African-American heavyweight Jack Johnson won his world title.” ~Gilbert King -SMITHSONIAN.COM

Taylor was born into poverty in Indianapolis on November 26 1878. Taylor was one of eight children in his family. His father Gilbert Taylor, Civil War veteran, and his mother Saphronia Kelter, had migrated from Louisville, Kentucky, with their large family to a farm in rural Indiana. Taylor Sr. worked as a coachman for the Southards, a wealthy Indiana family. Young Marshall often accompanied his father to work to help exercise some of the horses, and he became close friends with Dan Southard, the son of his father’s employer. By the time he was 8, the Southards had for all intents and purposes adopted him into their home, where he was educated by private tutors and virtually lived the same life of privilege as his friend Dan.

One of the Southard’s early gifts to Taylor was a new bike. Taylor took to it immediately, teaching himself bike tricks that he showed off to his friends. He became such an expert trick rider that a local bike shop owner, Tom Hay, hired him to stage exhibitions and perform cycling stunts outside his bicycle shop. Taylor received $6 a week, plus a free bike worth $35, for performing stunts while wearing a soldier’s uniform; hence the nickname “Major.”

Taylor entered his first bike race when he was in his early teens, a 10-mile event that he won easily. By the age of 18, he relocated to Worcester, Massachusetts, and started racing professionally. In his first competition, an exhausting six-day ride at Madison Square Garden in New York City, Taylor finished eighth. From there, he pedaled into history. By 1898, Taylor had captured seven world records. A year later, he was crowned national and international champion, making him just the second Black world champion athlete, after bantamweight boxer George Dixon. He collected medals and prize money in races around the world, including Australia, Europe and all over North America.

As his successes mounted, however, Taylor had to fend off racial insults and attacks from fellow cyclists and cycling fans. Though Black athletes were more accepted and had less overt racism to contend with in Europe, Taylor was barred from racing in the American South. Many competitors hassled and bumped him on the track, and crowds often threw things at him while he was riding. During one event in Boston, a cyclist named W.E. Becker pushed Taylor off his bike and choked him until police intervened, leaving Taylor unconscious for 15 minutes.

Exhausted by his grueling racing schedule and the racism that followed him, Taylor retired from cycling at age 32. Despite the obstacles, he had become one of the wealthiest athletes — black or whyte — of his time.

Sadly, Taylor found his post-racing life to be more difficult. While Taylor was reported to have earned between $25,000 and $30,000 a year, by the time of his death he had lost everything to bad investments (including self-publishing his autobiography), persistent illness, and the stock market crash. With his marriage over, he died at age 53 on June 21, 1932—a pauper in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, in the charity ward of Cook County Hospital—to be buried in an unmarked grave. He was survived by his daughter. (Taylor had married Daisy V. Morris in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21, 1902. While in Australia in 1904, Taylor and his wife had a daughter whom they named Sydney, in honor of the city in which she was born.)

Taylor’s body was exhumed in 1948 through the efforts of a group of former pro racers and Schwinn Bicycle Company owner Frank Schwinn, and moved to a more prominent area of the cemetery. A monument to his memory stands in front of the Worcester Public Library in Worcester, and Indianapolis named the city’s bicycle track after Taylor. Worcester has also named a high-traffic street after Taylor.

“Dedicated to the memory of Marshall W. ‘Major’ Taylor, 1878-1932. World’s champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and god-fearing, clean-living, gentlemanly athlete. A credit to the race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten.” ~Inscription on bronze marker on gravestone paid for by Frank W. Schwinn.

Taylor was posthumously inducted into the United States Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1989

Taylor’s daughter, Sydney Taylor Brown, died in 2005 at age 101; her survivors include a son and his five children. In 1984, Ms. Brown donated an extensive scrapbook collection on her father to the University of Pittsburgh Archives.

Quotes by Marshall “Major” Taylor

“I know that a good many champions have entertained the thought that the more they discourage youngsters, the longer they would reign. However, this theory never impressed me, and I always made it a point to give youths the benefit of my experience in bicycle racing. I always felt that good sportsmanship demanded that a champion in any line of sport should always be willing to give a helping hand to all worthy boys who aspire to succeed him.”

“Life is too short for any man to hold bitterness in his heart.”

“There are positively no mental, physical or moral attainments too lofty for the [African American] to accomplish if granted a fair and equal opportunity.”

“I trust they will use that terrible prejudice as an inspiration to struggle on to the heights in their chosen vocations.”

“A real honest-to-goodness champion can always win on the merits.”

Source:

http://www.biography.com/people/marshall-walter-major-taylor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Taylor

http://www.majortaylorassociation.org/who.shtml

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-unknown-story-of-the-black-cyclone-the-cycling-champion-who-broke-the-color-barrier-33465698/?no-ist

http://iammajortaylor.com/