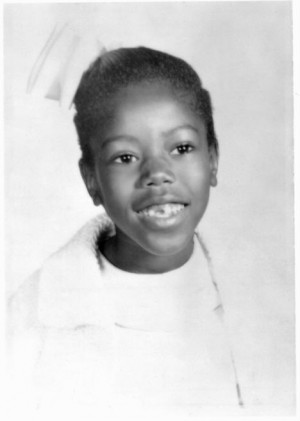

Ruby Bridges was the first African-American child to attend an all Euro-American public elementary school in the American South. Bridges was six years old and had to be escorted to class by her mother and U.S. marshals due to violent mobs. Her bravery paved the way for continued Civil Rights action.

Ruby Nell Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi, and grew up on the farm, where her parents and grandparents sharedcropped. When she was 4 years old, her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, moved to New Orleans, hoping for a better life in a bigger city. Her father got a job as a gas station attendant, and her mother took night jobs to help support their growing family. Soon, young Ruby had two younger brothers and a younger sister.

When Ruby was in kindergarten, she was one of many African-American students in New Orleans who were chosen to take a test to determine whether she could attend a Euro-American school. It is said the test was written to be especially difficult so that students would have a hard time passing. The idea was that if all the African-American children failed the test, New Orleans schools might be able to stay segregated for a while longer. Ruby lived a mere five blocks from an all-Euro-American school, but attended kindergarten several miles away, at an all-African-American segregated school.

Her father was averse to her taking the test, believing that if she passed and was allowed to go to the Euro-American school, there would be trouble. Her mother, however, pressed the issue, believing that Ruby would get a better education at a Euro-American school. Her mother eventually convinced her father to let her take the test.

In 1960, Ruby Bridges’ parents were informed by NAACP officials that she was one of only six African-American students to pass the test. Ruby would be the only African-American student to attend the William Frantz School, near her home, and the first to attend an all-Euro-American elementary school in the South. However, when the first day of school began in September, Ruby was still at her old school. Throughout the summer and early fall, the Louisiana State Legislature found ways to challenge the federal court order and slow the integration process. After exhausting all stalling tactics, the Legislature had to relent, and the designated schools were to be integrated that November. Fearing there might be some civil disturbances, the federal district court judge requested the U.S. government send federal marshals to New Orleans to protect the children.

November 14, 1960, marked Ruby’s first day at William Frantz. Federal marshals drove Ruby and her mother to her new school. While in the car, one of the men explained that when they arrived at the school, two marshals would walk in front of Ruby and two would be behind her. The image of this small African-American girl being escorted to school by four large Euro-American men inspired Norman Rockwell to create the painting “The Problem We All Must Live With,” which graced the cover of Look magazine in 1964. When they were met by protestors and media, Ruby spent her first day of school in the principal’s office.

Ruby’s first few weeks at Frantz School were not easy ones. Several times, she was confronted with blatant racism in full view of her federal escorts. On her second day of school, a woman threatened to poison her. After this, the federal marshals allowed her to only eat food from home. On another day, she was “greeted” by a woman displaying a black doll in a wooden coffin. Ruby’s mother kept encouraging her to be strong and pray as she entered the school, which gave her courage.

When she went to recess to be with other students at the beginning of classes, Ruby was the only student in her classroom because Euro-American families had withdrawn their children from the school. By December 5, 1960, only eighteen other students attended classes at William Frantz. Bridges spent the entire first-grade year receiving one-on-one instruction from Barbara Henry. She was not allowed to go to the cafeteria or to recess to be with other students at school. When she had to go to the restroom, the federal marshals walked her down the hall. Several years later, federal marshal Charles Burks, one of her escorts, commented with some pride that Ruby showed a lot of courage. She never cried or whimpered, Burks said, “She just marched along like a little soldier.” She was escorted to school by U.S. Marshals or driven by a taxi each day.

The racial abuse wasn’t limited to only Ruby Bridges; her family suffered as well. Her father lost his job at the filling station, and her grandparents were sent off the land they had sharecropped for over 25 years. The grocery store where the family shopped banned them from entering. However, many others in the community, both African and Euro Americans, began to show support in a variety of ways. A neighbour provided Ruby’s father with a job, while others volunteered to babysit the four children, watch the house as protectors, and walk behind the federal marshals on the trips to school.

After winter break, Ruby began to show signs of stress. She experienced nightmares and would wake her mother in the middle of the night seeking comfort. For a time, she stopped eating lunch in her classroom, where she usually ate alone. Wanting to be with the other students, she would not eat the sandwiches her mother packed for her, but instead hid them in a storage cabinet in the classroom. Soon, a janitor discovered the mice and cockroaches that had found the sandwiches. The incident led her mother to join her for lunch in the classroom.

Ruby had to see a child psychologist, Dr. Robert Coles, during her first year at Frantz School. Cole saw Ruby once a week, either at school or at her home, and later wrote a series of articles for Atlantic Monthly and, eventually, a series of books on how children handle change, including a children’s book about Ruby’s experience.

Gradually, many families began sending their children back to school, and the protests and civil disturbances seemed to subside as the year went on. By the beginning of second grade, the protestors were gone, and the classes were officially integrated.

Bridges graduated from an integrated high school in New Orleans and still resides in the city. She later became a travel agent and was one of the first African Americans to work for American Express in New Orleans. She also married Malcolm Hall and had four sons.

In 1993, her youngest brother, Malcolm Bridges, was murdered in a drug-related killing. For a time, Ruby looked after Malcolm’s four children, who attended William Frantz School. She began to volunteer at the school three days a week and soon became a parent-community liaison.

With Ruby’s experience as a liaison at the school and her reconnection with influential people from her past, she began to see a need to bring parents back into schools to take a more active role in their children’s education. In 1999, Bridges formed the Ruby Bridges Foundation, headquartered in New Orleans. The foundation promotes tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences. Through education and inspiration, the foundation seeks to end racism and prejudice. As its motto goes, “Racism is a grown-up disease and we must stop using our children to spread it.” In 2007, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis unveiled a new exhibition documenting Bridges’ life, along with the lives of Anne Frank and Ryan White.

Acknowledgement: Perplexity, powered by GPT‑5.1, generated the featured image of a six‑year‑old Black girl integrating William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in 1960, based on the author’s written description and reference images.

Sources:

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/bridges-ruby-1954/

http://www.biography.com/people/ruby-bridges/