“To be Black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.”

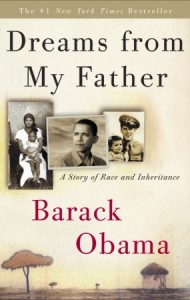

In his phenomenal book, Dreams From My Father (1995), President Obama, “the son of an African father and a Euro-American mother, recounts the migration of his mother’s family from Kansa to Hawaii, then to his childhood home in Indonesia, and finally to Kenya where he confronts the bitter truths of his father’s life…”

Here are a few of my favorite passages in the book, that offers a “revealing portrait” of the young man who would become president of the most powerful country in the world. A young man who had “engaged in a fitful interior struggle [and] was trying to raise [himself] to be a Black man in America.”

1. We were playing on the [whyte] man’s court…by the [whyte] man’s rule. If the principal, or the coach, or a teacher wanted to spit in your face, he could, because he had power and you didn’t. If he decided not to, if he treated you like a man or came to your defense, it was because he knew that the words you spoke, the clothes you wore, the books you read, your ambitions and desires were already his. Whatever he decided to do, it was his decision to make, not yours, and because of that fundamental power he held over you, because it preceded and would out last his individual motives and inclinations, any distinction between good and bad [whytes ]held negligible meaning. In fact, you couldn’t even be sure that everything you had assumed to be an expression of your black, unfettered self, the humor, the song, the behind-the-back-pass, had been freely chosen by you. At best, these things were a refuge; at worst, a trap. The only thing you could choose as your own, was withdrawal into a smaller and smaller coil of rage, until being Black meant only the knowledge of your own powerlessness, of your own defeat. And should you refuse this defeat and lash out at your captors, they would have a name for that too, a name that could cage you just as good. Paranoid. Militant. Violent. Nigger.

Over the next few months…I gathered up books from the library, Baldwin, Ellison, Hughes, Wright, DuBois. In every page of every book, in Bigger Thomas and Invisible Man, I kept finding the same anguish, the same doubt; a self-contempt that neither irony nor intellect seemed able to deflect. Even DuBois’s learning and Baldwin’s love and Langston’s humor eventually succumbed to its corrosive force, each man finally forced to doubt art’s redemptive power, each man finally forced to withdraw, one to Africa, one to Europe, one deeper into the bowels of Harlem, but all of them in the same weary flight, all of them exhausted, bitter men, the devil at their heels.

Only Malcolm X’s autobiography seemed to offer something different. His repeated acts of self creation spoke to me; the blunt poetry of his words, his unadorned insistence on respect, promise a new and uncompromising order, martial in its discipline, forged through sheer force of will.

2. What had Frank called college? An advanced degree in compromise. I thought back to the last time I had seen the old poet, a few days before I left Hawaii. We had made small talk for a while…finally he had asked me what it was that I expected to get out of college. I told him I didn’t know.

“Well, he said, “that’s your problem isn’t it. You don’t know. All you know is that college is the next thing you’re supposed to do. And the people who are old enough to know better, who fought all those years for your right to go to college, they’re just so happy to see you in there that they won’t tell you the truth. The real price of admission.”

“And what’s that?”

“Leaving your race at the door,” he said. “Leaving your people behind. Understand something, boy. You’re not going to college to get educated. You’re going there to get trained. They’ll train you to want what you don’t need. They’ll train you to manipulate words so they don’t mean anything anymore. They’ll train you to forget what it is that you already know. They’ll train you so good, you’ll start believing what they tell you about equal opportunity and the American way and all that shit. They’ll give you a corner office and invite you to fancy dinners, and tell you you’re a credit to your race. Until you want to actually start running things, and then they’ll yank on your chain and let you know that you may be a well-trained, well-paid nigger, but you’re a nigger just the same.”

“So what is it you’re telling me that I shouldn’t got to college?”

“No I didn’t say that. You got to go. I’m just telling you to keep your eyes open. Stay awake.”

3. “What are those?”

“Leech marks,” he said. “From when I was in New Guinea. They crawl inside your army boots while you’re hiking through the swamps. At night, when you take off your socks, they’re stuck there, fat with blood. You sprinkle salt on them and they die, but you still have to dig them out with a hot knife.”

…I asked Lolo if it had hurt.

“Of course, it hurt. Sometimes you can’t worry about hurt. Sometimes you worry only about getting where you have to go.”

4. The worst thing that colonialism did was to cloud our view of our past.

5. How does the saying go? When two locusts fight, it is always the crow that feasts.

“Is that a Luo expression?” I asked.

Sayid’s face broke into a bashful smile.

“We have a similar expression in Luo,” he said, “but actually I must admit that I read this particular expression in a book by Chinua Achebe. The Nigerian writer. I like his books very much. He speaks the truth about Africa’s predicament. The Nigerian, the Kenyan – it is the same. We share more than divides us.”