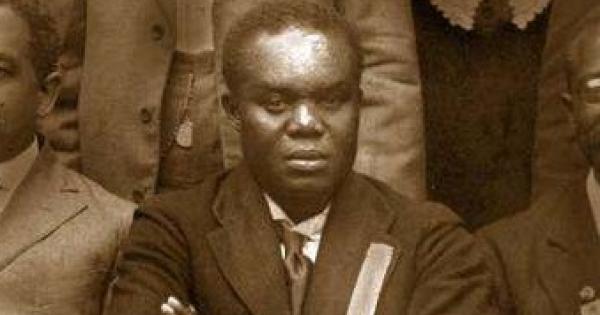

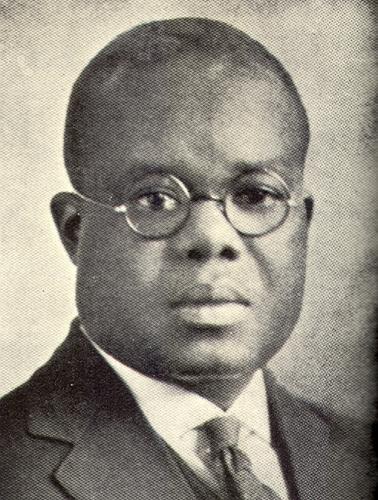

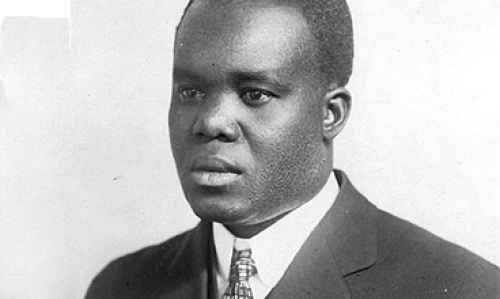

Born April 27, 1883, in Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, Hubert H. Harrison was a brilliant and influential writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist in Harlem during the early decades of the 20th century. He played unique, signal roles, in what were the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the New Negro/Garvey movement) of his era. Labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph described him as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and historian Joel A. Rogers considered him “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” and “one of America’s greatest minds.”

Harrison’s first seventeen years on St. Croix provided a firm foundation for his future work. In St. Croix he became familiar with important traditions “rooted in the African communal system” (including free public gardens and Saturday markets) which mitigated some of the oppressive pressures of the capitalist economy on laboring families. He learned of the Crucian people’s rich history of direct action mass struggle including the 1848 enslaved-led emancipation victory and the 1878, week-long, island-wide, labor protest known as “The Great Fireburn” (led by rebel leaders “Queen Mary” Thomas, “Queen Agnes” and “Queen Matilda”). He also came to know poverty, and that experience, he said, helped to keep his “heart open to the call of those who are down” and kept him from developing “such airs as might make a chasm between myself and my people.”

Interestingly and instructively, Harrison claimed that as a youth he knew nothing of the “doctrine of chromatic inferiors and superiors” which was “violently thrust upon the islanders” by the occupying U.S. Navy after the United States purchased the Danish West Indies in 1917. Due to different historical particulars, class struggle, and social control, the color line and “race relations” in St. Croix differed from those in the United States. In St. Croix there was a historic policy of promotion of a sector of the African-descended population (under slavery, Crucian “coloreds” were the key to the social control force, served in the militia, and were extended an edict of full equality in 1834). In the United States laboring “whites,” not “coloreds,” were the historic key social control force, and the general rule under slavery (as described in the 1857 Dred Scott decision) was one of severe racial proscription for the African-descended population (African Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect”). The extension and development of these differences took such form that the St. Croix of Harrison’s youth did not have the lynching, formal segregation, virulent white supremacy, or severe racial proscriptions against advancement for those of African descent that Harrison would encounter in the United States.

These differences help to explain why Harrison was provided more encouragement to pursue his educational interests in St. Croix than was afforded the overwhelming majority of African American youth in the southern United States.

He used the library at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Christiansted, studied under one of the island’s best teachers (Wilfurd Jackson, whose son, D. Hamilton Jackson, was Harrison’s friend and schoolmate, and became the island’s foremost labor leader), and excelled enough as a student that he was chosen as a teaching assistant. These differences also help to explain why Harrison would challenge the virulent white supremacy he encountered in the United States. When he left for the U. S., though virtually penniless, the fires of learning were burning and Harrison believed he was the equal of any other.

Shortly after his mother died Harrison immigrated to the United States, arriving in 1900 as a 17-year-old orphan. His move from the rural, agricultural island of St. Croix to the teeming urban/industrial metropolis of New York was truly a move from the 19th into the 20th century. His arrival coincided with U.S. capitalism’s ascent to new imperialist heights, with the period of intense racial oppression of African Americans known as the “nadir,” and with the era of critical writing and muckraking journalism that, according to one social commentator, produced “the most concentrated flowering of criticism in the history of American ideas.” These factors would play an important part in shaping the remainder of his life.

In 1917 Harrison organized and became president of the Liberty League, a militant, all-black organization devoted to equal rights. He wrote for The Voice, the newspaper of the Liberty League, where he denounced Jim Crow laws and lynching. Two years later, in 1919, Harrison founded The New Negro, a newspaper he dedicated to denouncing the murderous race riots and lynching across America. Harrison’s New Negro popularized the term “New Negro,” which urged African Americans to physically fight back against their white oppressors and permanently discard the obsequious image popularly attributed to them by the white media.

By 1920, Hubert Harrison found his newspaper and his organizing efforts overshadowed by another West Indian immigrant, Marcus Garvey, and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Though never officially joining the UNIA, Harrison accepted a position as editor for Negro World, the UNIA newspaper. He worked for Negro World for two years before breaking with Garvey in 1922. Eventually Harrison would join other African American leaders in signing a petition calling for Garvey’s deportation by the Federal government.

After leaving Negro World Harrison continued to lecture and write editorials for black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier. Referred to by many as the “Black Socrates,” Harrison never received a college degree.

In the 1920s, after breaking with Garvey, Harrison continued his full schedule of activities. He lectured on a wide range of topics for the New York City Board of Education and for its “Trends of the Times” series, which included prominent professors from the city’s foremost universities. His book and theater reviews and other writings appeared in many of the leading periodicals of the day- including the New York Times, New York Tribune, New York World, Nation, New Republic, Modern Quarterly, Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender, Amsterdam News, Boston Chronicle, and Opportunity magazine. He also spoke against the revived Ku Klux Klan and the horrific attack on the Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black community, and he worked with numerous groups, including the Virgin Island Congressional Council, the Democratic Party, the Farmer-Labor Party, the single tax movement, the American Friends Service Committee, the Urban League, the American Negro Labor Congress, and the Workers (Communist) Party.

One of his most important activities in this period was the founding of the International Colored Unity League (ICUL) and its organ, The Voice of the Negro. The ICUL was Harrison’s most broadly unitary effort (particularly in terms of work with other Black organizations and with the Black church). It urged Blacks to develop “race consciousness” and its 1924 platform had political, economic, and social planks urging protests, self-reliance, self-sufficiency, and collective action. It also included as its “central idea” the founding of “a Negro state, not in Africa, as Marcus Garvey would have done, but in the United States,” as an outlet for “racial egoism.” It was a plan for “the harnessing” of “Negro energies” and for “economic, political and spiritual self-help and advancement” (which preceded a somewhat similar plan by the Communist International by four years).

Overall, in his writing and oratory, Harrison’s appeal was both mass and individual. He focused on the man and woman in the street and emphasized the importance of each individual’s development of an independent, critical attitude. The period during and after World War I was one of intense racial oppression and great Black migration from the South and the Caribbean into urban centers, particularly in the North. Harrison’s race-conscious mass appeal utilized newspapers, popular lectures, and street-corner talks and marked a major shift from the leadership approaches of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Harrison’s affective appeal (later identified with that of Garvey) was aimed directly at the urban masses and, as the Harlem activist Richard B. Moore explained, “More than any other man of his time, he [Harrison] inspired and educated the masses of Afro-Americans then flocking into Harlem.”

Though he was extremely popular among the masses who “flocked to hear him,” Harrison, according to Rogers, was often overlooked by “the more established conservative Negro leaders, especially those who derived support from wealthy whites.” Others, “inferior… in ability and altruism, received acclaim, wealth, and distinction” that was his due.

In his last lecture, Harrison told his listeners that he had appendicitis and would be getting surgery. Afterwards, he said he would be giving another lecture. He died on December 17, 1927 on the operating table, at the age of 44.

When he died the Harlem community, in a major show of affection, turned out by the thousands for his funeral. A church was (ironically) named in his honor and his portrait was to be placed prominently at the 135th Street Public Library, where he, along with the bibliophile Arthur Schomburg and others, had helped to found and develop the world-famous “Department of Negro Literature and History.”

Sources:

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/archival/collections/ldpd_6134799/

Hubert Harrison (1883-1927): Race Consciousness and the Struggle for Socialism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_Harrison