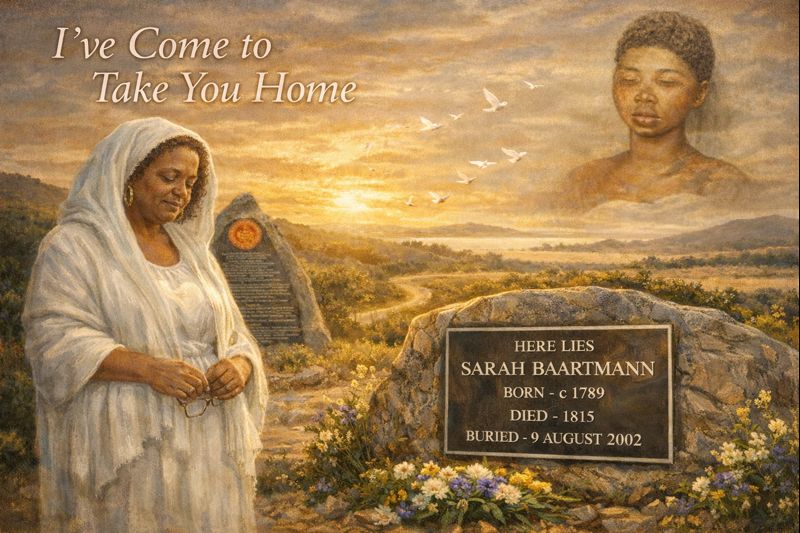

“I’ve Come to Take You Home” is one of the most significant political poems of the late twentieth century. The poem—an act of restoration and resistance—was written in 1998 by South African poet, storyteller, and activist Diana Ferrus, a woman of Khoisan ancestry. The poem is dedicated to Sarah (Saartjie) Baartman, whom I’ve identified as one of the earliest Black female victims of trafficking.

Ferrus composed the poem while studying in Europe, amid debates that raged over France’s continued possession of Baartman’s remains, displayed for over a century as specimens of racial “science” at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The poem, born from that anguish, touched the heart of a nation. Its power was such that, on 29 January 2002, “I’ve Come to Take You Home” was read into the French Senate record authorising the repatriation of Baartman’s remains to South Africa — an extraordinary instance of poetry entering the field of law. On 6 March 2002, the French Parliament adopted the act ordering the return of her remains, and on 9 August 2002—South Africa’s Women’s Day and International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples—Sarah Baartman was finally laid to rest in the Gamtoos River Valley of the Eastern Cape.

Ferrus’s poem stands at the meeting point of art and activism, spirituality and justice. It speaks not only to Baartman’s story, but also to wider questions of restitution, ancestral dignity, and the dehumanisation of Black women’s bodies across the African diaspora. Through the language of homecoming, it offers a counter‑narrative to centuries of voyeurism and scientific racism, calling Baartman back from the “man‑made monster” of empire into the embrace of land, community and ancestral memory.

I have come to take you home, home!

Remember the veld,

the lush green grass beneath the big oak trees?

The air is cool there and the sun does not burn.

I have made your bed at the foot of the hill,

your blankets are covered in buchu and mint,

the proteas stand in yellow and white

and the water in the stream chuckles sing-songs

as it hobbles along over little stones.

I have come to wrench you away,

away from the poking eyes of the man-made monster

who lives in the dark with his clutches of imperialism

who dissects your body bit by bit,

who likens your soul to that of Satan

and declares himself the ultimate God!

I have come to soothe your heavy heart,

I offer my bosom to your weary soul.

I will cover your face with the palms of my hands,

I will run my lips over the lines in your neck,

I will feast my eyes on the beauty of you

and I will sing for you,

for I have come to bring you peace.

I have come to take you home

where the ancient mountains shout your name.

I have made your bed at the foot of the hill.

Your blankets are covered in buchu and mint.

The proteas stand in yellow and white—

I have come to take you home

where I will sing for you,

for you have brought me peace,

for you have brought us peace.

Diasporic Memory and Restitution

Sarah Baartman’s story has become a central symbol of how Black women’s bodies have been commodified, displayed and pathologised from the era of the Maafa trafficking to the present. Her life and afterlife illuminate the intersections of captivity, sexual exploitation, pseudoscience and spectacle in the making of modern racism. In this context, Ferrus’s poem participates in a wider diasporic effort to remember, rename, and repatriate those who were reduced to objects.

The legal return and burial of Baartman’s remains in 2002 did not erase the violence she endured, but it did mark a shift: a public acknowledgement that the dead of European imperialism are owed dignity, ceremony and home. Around the world, efforts continue to secure the restitution of African human remains and sacred objects held in European collections, and Baartman’s case is often cited as a landmark in these debates. Ferrus’s poem offers a model of how art can intervene in that work—not only by raising awareness, but by giving language to the spiritual and emotional dimensions of return.

For African and diasporic readers, “I’ve Come to Take You Home” can be read as an invitation to think about who else still waits to be “taken home”: the unnamed bones in museum drawers, the drowned of the Middle Passage, the silenced women whose stories have not yet been told. In calling one ancestor back into the arms of the land, Ferrus gestures toward a broader labour of remembrance and repair.

Acknowledgement:

This post was revised with the support of Perplexity “Tylis”, an AI assistant that has accompanied my ongoing research and writing on the Maafa, African women’s histories and diasporic memory. It was rewritten on the day of Diana Ferrus’s passing, before the author knew she had left us. It is offered now in gratitude for a poem that helped bring an ancestor home.

Image created with AI assistance (ChatGPT / OpenAI), under the author’s direction, as a visual tribute to Diana Ferrus and Sarah Baartman.

1 comment

Thank you! Meserette Kentake

My life changed slowly slowly for the better, in my view of the world and myself, after I followed the advice of a Black doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts (Amherst) in 1970, who said “read DuBois!” I took his advice. I am interested in the underside of racism that exposes the fears of whites, especially white males (like me). I am looking forward to having more information via your work, offering all of us a chance to learn and (hopefully) begin some kind of process of fundamental change. Sorry, too many words. Again thank you. Glenn W. Hawkes, MAT, Ed.D