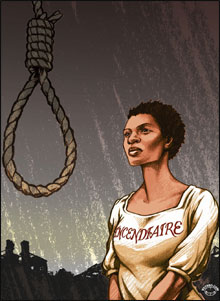

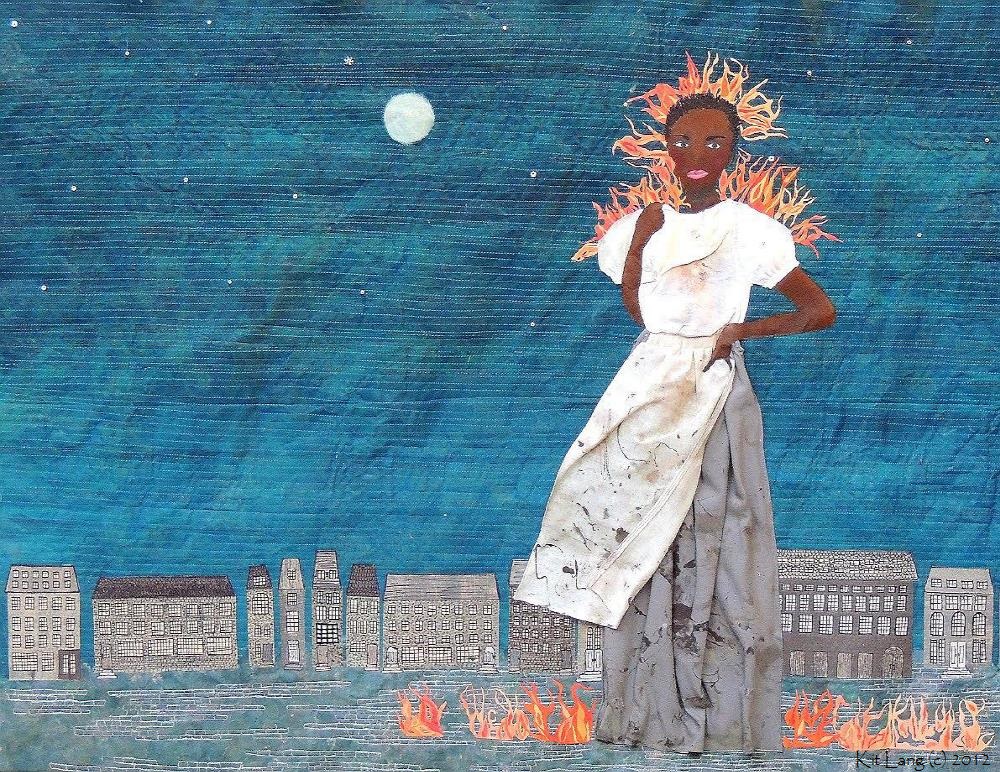

In 1734, Marie-Joseph Angélique was accused of setting a fire that destroyed the city’s merchants’ quarter in Montreal. Authorities claimed that Angélique started the blaze in an attempt to escape captivity. She was subsequently convicted, tortured, and executed by hanging on June 21, 1734. Although it remains uncertain whether she was truly responsible for the fire, Angélique’s story endures as a powerful symbol of resistance and the struggle for freedom.

Angélique was born around 1705 on the island of Madeira, Portugal. Few details are known about her early life, but it is believed she was first held in Portugal, which was an active hub in the Atlantic trafficking. As a teenager, Angélique was likely sold to the Flemish merchant Nichus Block. She was then transported by ship to North America, possibly passing through Flanders (in present-day northern Belgium), an area with strong trading connections to Portugal.

Angélique was sent back to the widow Francheville, and her intended escape went unpunished. Thibault, by contrast, was imprisoned. Angélique continued to visit him during his imprisonment, providing him with food and support, despite her mistress’s disapproval. Thibault was released two months later, on April 8th, 1734, two days before the fire of Montreal.

Soon after, Angélique ran away with Thibault. Her intent was to return to Portugal, the land of her birth. The couple set fire to Angélique’s bed at Alexis Monière’s home — where Francheville had chosen to move them temporarily — and fled in the direction of New England, where they hoped to catch a ship bound for Europe. Two weeks later, Angélique and Thibault were tracked down by the police in nearby Chambly. Angélique was returned to her captor to await transport to Québec City, and Thibault was imprisoned. Upon returning to Montréal, Angélique reiterated that she would burn down the house because she wanted to be free.

On the evening of Saturday, 10 April 1734, a large portion of Montréal — the merchants’ quarter — was destroyed by fire. At least 46 buildings, mainly homes, were burnt, plus the convent and hospital of the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. Angélique was accused of starting the fire and arrested by the police on 11 April. She was taken to court the following morning, where she was charged with arson, a capital crime punishable by death, torture or banishment. In the French legal system of the 18th century, the accused was presumed guilty, and in New France, there were no trials by jury; instead, there were inquisitorial tribunals in which the defendant was required to prove her innocence. Lawyers were banned from practising in the colony by Louis XIV.

See also: Ten Iconic Black Women of the Maafa

Sources:

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca-en/article/marie-joseph-angelique/

http://activehistory.ca/2012-09-marie-joseph-angelique-remembering-the-arsonist-slave-of-montreal/

Acknowledgement: This post was updated on 7th February 2026. The featured image was created by ChatGPT under the author’s direction.