“A normal black child, having grown up in a normal family, will become abnormal at the slightest contact with the [whyte] world.”

Frantz Fanon was a psychiatrist, originally from Martinique. A revolutionary political thinker, he became a spokesman for the Algerian revolution against French colonialism. His book The Wretched of the Earth (1961) is seen as the “bible of Third Worldism.” Fanon also developed some important insights into the ideological aspects of racialism and Black consciousness. His 1952 book, Black Skin, White Masks, offers a penetrating psychological analysis of racism and of the ways in which it is internalized by its victims. Fanon’s books are seen as a major influence upon subsequent generations of thinkers, activists, and liberation movements. As Eldridge Cleaver put it, “Every brother on a rooftop can quote Fanon.” Fanon succumbed to leukemia at the young age of 36, a year before Algeria’s independence in 1962.

Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique on July 20, 1925. His father was a descendant of enslaved Africans, and his mother was said to be an “illegitimate” child of African, Indian, and European descent, whose whyte ancestors came from Strasbourg in Alsace. Fanon’s family was socio-economically middle-class and they could afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, then the most prestigious high school in Martinique. Fanon’s political awakening began as a 14-year-old when in 1939, he had the good fortune to have Aimé Césaire – Martinique’s other renowned critic of European colonization – as a high school teacher.

“It was the first time I saw that the history they were teaching us was based on a denial, that the order of things we were being presented with was a falsehood. I still played and took part in sports and went to the movies, but everything had changed. I felt as though my eyes and my ears had been opened.”

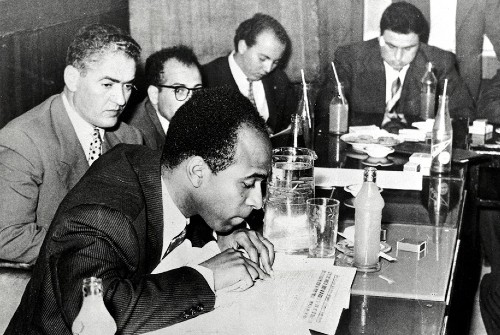

Frantz Fanon at a press conference of writers in Tunis, 1959

Frantz Fanon walking up a ship gangway

Frantz Fanon and M’Hamed Yazid representing the Algerian National Liberation Front at the Pan-African conference

A Protest. Image by désinterest via Flickr

Politicized, Fanon left the colony in 1943, at the age of 18, to fight with the Free French forces, and was awarded a Croix de Guerre after sustaining a serious shrapnel wound in the chest. After the war, he stayed in France, completing his studies in medicine and psychiatry at the University of Lyon. Embittered by the racism he encountered Fanon gravitated to radical politics, Sartrean existentialism, and the philosophy of Black consciousness known as negritude, which inspired him to write his first book. Black Skin, White Masks, was published in 1952 when Fanon was only 27 years old. Originally, Black Skin, White Masks was a doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled “Essay on the Disalienation of the Black”. However, when it was rejected, it prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. “The book deals with the lived experience of being Black in an anti-Black world. It begins in Martinique and moves to France examining language, sexual desire, embodied presence in the world, psychology, and the politics of recognition in the light of the social fact that blackness assumes in a racist society.”

He briefly returned to the Caribbean after he finished his studies, before accepting a position as chef de service (chief of staff) for the psychiatric ward of the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria. The following year, 1954, marked the eruption of the Algerian war of independence against France, an uprising directed by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and brutally repressed by French armed forces. While treating Algerians and French soldiers, Fanon began to observe the effects of colonial violence on the human psyche. Witnessing the unspeakable suffering inflicted by the French Army, he came to believe that the revolution contained the seeds of redemption, not only for Algeria but for the entire colonial world.

By 1956 Fanon realized he could not continue to aid French efforts to put down a decolonization movement that commanded his political loyalties, and he resigned his position at the hospital. He began working with the Algerian liberation movement, the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale; FLN), and in 1956 became an editor of its newspaper, El Moudjahid. During this period, he was based primarily in Tunisia, where he founded Africa’s first psychiatric clinic and wrote several influential essays on decolonization. Some of Fanon’s writings from this period were published posthumously in 1964 as Toward the African Revolution. In 1959 Fanon published a series of essays, The Year of the Algerian Revolution, which detail how the oppressed natives of Algeria organized themselves into a revolutionary fighting force.

In 1960 he was appointed ambassador to Ghana by Algeria’s FLN-led provisional government, travelling throughout Africa as a spokesman for the revolution. It was in Ghana that Fanon was diagnosed with the leukemia. He immediately decided to write a new book, his last. That book, The Wretched of the Earth, was written in ten weeks. In October 1961, Fanon was brought to the United States by a C.I.A. agent so that he could receive treatment at a National Institutes of Health facility in Bethesda, Maryland. He died two months later, on December 6, 1961, reportedly still preoccupied with the cause of liberty and justice for the peoples of the Third World. At the request of the FLN, his body was returned to Tunisia, where it was subsequently transported across the border and buried in the soil of the Algerian nation for which he fought so single-mindedly during the last five years of his life.

Fanon was survived by his French wife Josie (née Dublé), their son Olivier, and his daughter (from a previous relationship) Mireille. Josie took her own life in Algiers in 1989. Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in international law and conflict resolution. She has also worked for UNESCO and the French National Assembly, and she serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier married Valérie Fanon-Raspail, who manages the Fanon website.

Featured image credit: Franz Fanon (2018) retrieved from (and is for sale at) https://www.artsper.com/en/contemporary-artworks/painting/303784/frantz-fanon

Source:

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/02/books/review-02SHATZTW.html

https://www.todayinliterature.com/stories.asp?Event-Date=12/6/1961

https://www.iep.utm.edu-fanon/

https://repeatingislands.com-2011/06/20/frantz-fanon-50-years-on/