[dropcap size=small]B[/dropcap]ooker Taliaferro Washington was an African-American leader and educator. Washington came up from a background of poverty to become the most influential Black educator of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the successor of Frederick Douglass. In 1881, he founded the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama (now known as Tuskegee University).

Booker T. Washington was born on April 5, 1856, in Franklin County, Virginia, on a “pile of rags on the dirt floor of a kitchen cabin.” His mother, Jane, was an enslaved cook, who named him Booker Taliaferro. He never knew who his father was, except that he was someone in the neighborhood. Washington had medium brown skin, reddish hair and luminous gray eyes, which made many believed that his father was of European descent. His surname was taken years later from his stepfather. Washington’s elder brother, John, was born four years before him, also of an unknown father. Some time after his birth, his mother was married to Washington Ferguson, an enslaved man. A daughter, Amanda, was born to this marriage. James, his younger half-brother, was adopted.

Washington spent his first nine years enslaved on the Burroughs farm where he was born. The last four of those nine years were during the Civil War. Washington remembers that his mother leaned over and kissed her children, while “tears of joy ran down her cheeks” after Emancipation. In 1865, his mother took her children to Malden, West Virginia, to join her husband, who had gone there earlier and found work in the salt mines. At age nine, Washington was put to work packing salt and between the ages of ten and twelve, he worked in a coal mine; while still attending school. In 1871, he went to work as a houseboy for the wife of the owner of the mines, who had a reputation for being very strict with her servants, especially boys. But over the two years he worked for her, he was able to attend school for an hour a day during the winter months.

When Washington heard about the Hampton Institute, for African-Americans, he decided at once to attend it, and at age sixteen, he entered Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia. The journey to Hampton was nearly five hundred miles. After Washington’s railroad ticket had run its distance, he took the stagecoach, and then had to walk or accept free rides on passing wagons and buggies. It was on this trip that Washington experienced the sharpest edge of racial bias when he was not allowed in a hotel, as the lone African-American passenger on the stagecoach. He walked and shivered in the cold outside until morning.

His entrance examination to Hampton was to clean a room. He swept the room three or four times and dusted it an equal number. The teacher inspected his work with a spotless, white handkerchief. Admitted to Hampton, he was given work as a janitor to pay the cost of his room and board. Washington’s years at Hampton became the central shaping experience of his life. It was here he met General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, head of Hampton, who would exert a major influence over his life. Washington became a star pupil under the tutelage of General Armstrong, and graduated from Hampton with honors in 1875.

After graduating, Washington returned to Malden to teach. For eight months he was a student at Wayland Seminary, an institution with a curriculum that was entirely academic. This experience reinforced his belief in an educational system that emphasized practical skills and self-help. In 1879, Washington returned to Hampton to teach in a program for American Indians.

In 1880, a bill that included a yearly appropriation of $2,000 was passed by the Alabama State Legislature to establish a school for African-Americans in Macon County. This action was generated by two African-American men – Lewis Adams and George W. Campbell. On February 12, 1881, Governor Rufus Willis Cobb signed the bill into law, establishing the Tuskegee Normal School for the training of Black teachers. General Armstrong was invited to recommend a Euro-American teacher as principal of the school. Instead, he suggested Washington, who was accepted.

When Washington arrived at Tuskegee, he found that no land or buildings had been acquired for the projected school, nor was there any money for these purposes since the appropriation was for salaries only. Undaunted, Washington began selling the idea of the school, recruiting students and seeking support.

The institute opened on July 4, 1881, with one teacher and thirty pupils in a shanty loaned by a Black church, Butler A.M.E. Zion. However, when the institute celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary it owned 2,000 acres of land and eighty-three large and small buildings, which, with its equipment of live stock, stock in trade, and other personal property, were valued at $831,895. This did not include 22,000 acres of public land remaining unsold from the 25,000 acres granted by Congress, valued at $135,000, nor the endowment fund, which was $1,275,644. There were also more than 1,500 students enrolled in the school — more than 1,000 young men, and more than 500 young women. The students were trained in thirty-seven industries and followed a rigid schedule of study and work, arising at five in the morning and retiring at nine-thirty at night. Although Tuskegee was non-denominational, all students were required to attend chapel daily and a series of religious services on Sunday. Washington himself usually spoke to the students on Sunday evening.

Olivia Davidson, a graduate of Hampton and Framingham State Normal School in Massachusetts, became teacher and assistant principal at Tuskegee in 1881. In 1885, Washington’s older brother John, also a Hampton graduate, came to Tuskegee to direct the vocational training program. Other notable additions to the staff were acclaimed scientist Dr. George Washington Carver, who became director of the agriculture program in 1896; Emmett J. Scott, who became Washington ‘s private secretary in 1897; and Monroe Nathan Work, who became head of the Records and Research Department in 1908.

Through progress at Tuskegee, Washington showed that an oppressed people could advance. His concept of practical education was a contribution to the general field of education. His writings, which included 40 books, were widely read and highly regarded.

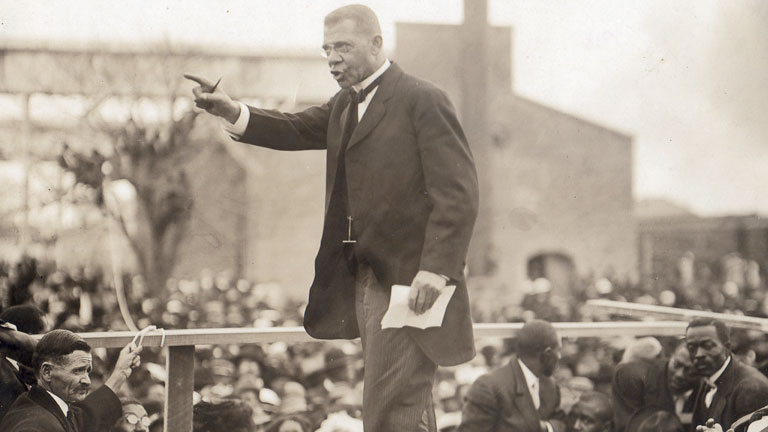

In September 1895, Washington became a national hero when he gave a controversial speech about “The New Negro,” one with “the knowledge of how to live, how to cultivate the soil, to husband their resources, and make the most of their opportunities.” Invited to speak at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Washington publicly accepted disfranchisement and social segregation as long as whytes would allow black economic progress, educational opportunity, and justice in the courts. Washington stated that, “The wisest of my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than to spend a dollar in an opera house.”

Word of his aims spread all over the country, and soon Euro-American men and women of means began to assist his ambition. Chief among these was Andrew Carnegie, who began by giving a $20,000 library to the institute, which he followed with a regular contribution of $10,000 a year. The climax of Mr. Carnegie’s generosity toward the institute was reached in 1903, when he gave $600,000 to the endowment fund.

Washington further publicized himself and his program by publishing his autobiography, Up From Slavery in 1901. He also founded the National Negro Business League in 1900. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, both men with deep racial prejudices, endorsed and supported Washington as an advisor because he accepted racial segregation. Washington was able to recommend candidates for minor political posts that traditionally were given to African-Americans. The industrialists who controlled the financing of many Black schools in the South depended upon his advice as to which schools should receive funds. Though he never seemed to seek them, honors of all kinds were bestowed upon him. The degree of M. A. was conferred upon him by Harvard in 1896, and LL. D. by Dartmouth in 1901. On Oct. 16, 1901, Washington became the first Black person to dine at the White House on the invitation of President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1910, when Washington was in Europe, he was received by the King of Denmark, addressed the National Liberal Club in London, and visited Mr. Carnegie in Skibo Castle.

However, Washington’s policies received a challenge from within the Black community. W.E.B. Du Bois, then a scholar at Atlanta University, attacked Washington’s philosophy in the book , The Souls Of Black Folk. An organized resistance to Washington grew within the African-American intellectual community. But as far as the majority of middle-class and working-class African-Americans were concerned, Washington remained their man of the hour. His popularity enabled him to neutralize criticism, sometimes by by reporting false and unflattering reports of his critics to newspapers. Because of his image as a conciliator, Washington seldom could publicly criticize injustice. Yet, behind the scenes, he did finance court cases challenging segregation and tried to mitigate some of its excesses.

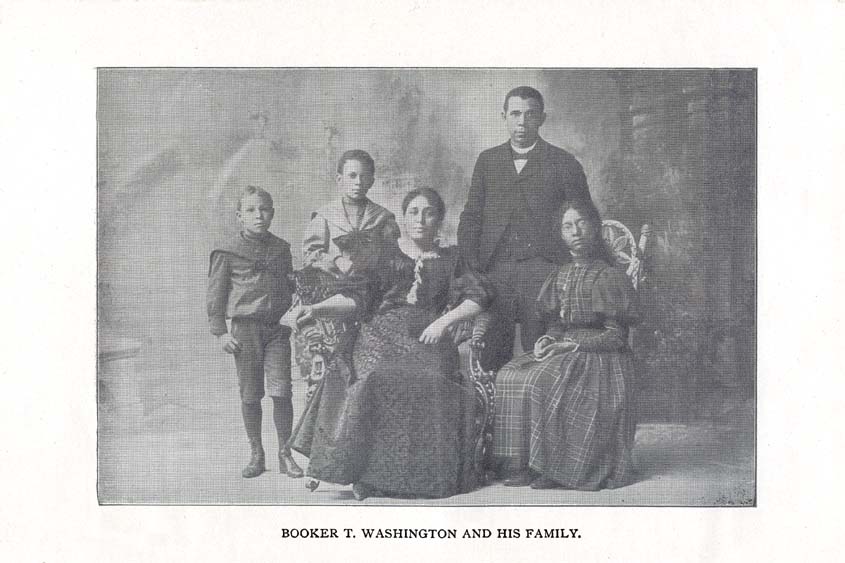

Washington was married three times. In 1882, he married his Malden sweetheart, Fannie N. Smith. She died two years later, leaving an infant daughter, Portia (who married William Sidney Pittman, an architect, in 1907).

Washington was married three times. In 1882, he married his Malden sweetheart, Fannie N. Smith. She died two years later, leaving an infant daughter, Portia (who married William Sidney Pittman, an architect, in 1907).

In 1885, Washington married Olivia Davidson, the assistant principal of Tuskegee, who died in 1889. Two sons were born to this marriage: Booker Taliaferro, Jr. and Ernest Davidson. In 1893, Washington was married to Fisk University graduate Margaret Murray, who had come to Tuskegee as lady principal in 1889 and directed the programs for female students and initiated the Women’s Meetings.

Margaret and her husband’s three children and four grandchildren survived Washington, who died November 14, 1915, at age fifty-nine of arteriosclerosis and exhaustion. He died after an illness in St. Luke’s hospital, New York City, where he had been admitted on November 5. Aware that the end was near, he left the hospital with his wife and his physician on November 12, so that he could die in Tuskegee.

Washington’s November 17 funeral in the Tuskegee Institute Chapel was attended by nearly 8,000 people. He was buried in a brick tomb, made by students, on a hill commanding a view of the entire campus.

Source:

http://www.tuskegee.edu/about_us/legacy_of_leadership/booker_t_washington.aspx

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_people_booker.html