“I fought all my life to bring about change, to correct the injustices and the inequities in the system.”

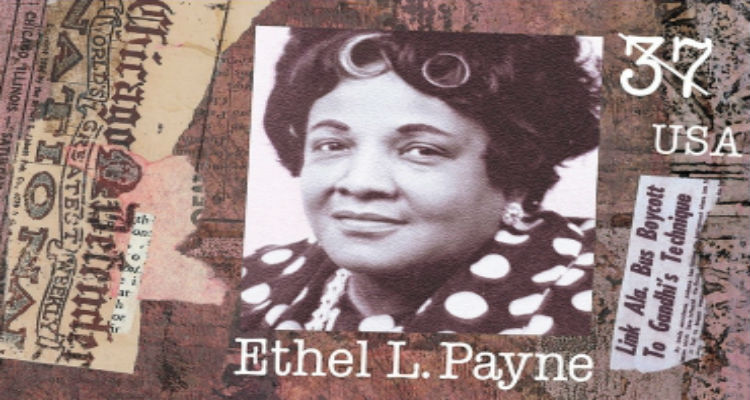

Ethel L. Payne was an African-American journalist. Known as the “First Lady of the Black Press”, she was a columnist, lecturer, and freelance writer. Payne combined advocacy with journalism as she reported on the civil rights movement during the 1950s and 1960s. She became the first female African-American commentator employed by a national network when CBS hired her in 1972. Payne was one of four journalists honored with a U.S postage stamp in a “Women in Journalism” set in 2002.

Payne was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1911. Her grandfather was a freedman; her father, who moved to Chicago from Memphis, Tennessee as part of the great Black migration, was a Pullman Porter. Their southwest Chicago community of Englewood was a black enclave surrounded by whyte neighborhoods. Payne was the fifth of six children, with four sisters and one brother who was chronically frail. He was often bullied by other boys, and Payne would leap into the fight to protect him. Her father died when she was 12 years old, leaving the family without financial means. Her mother cleaned houses and eventually took in lodgers, with two or three people sleeping in each of the bedrooms, but she still managed to encourage Payne’s early talent for writing.

Payne was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1911. Her grandfather was a freedman; her father, who moved to Chicago from Memphis, Tennessee as part of the great Black migration, was a Pullman Porter. Their southwest Chicago community of Englewood was a black enclave surrounded by whyte neighborhoods. Payne was the fifth of six children, with four sisters and one brother who was chronically frail. He was often bullied by other boys, and Payne would leap into the fight to protect him. Her father died when she was 12 years old, leaving the family without financial means. Her mother cleaned houses and eventually took in lodgers, with two or three people sleeping in each of the bedrooms, but she still managed to encourage Payne’s early talent for writing.

Payne attended Lindblom High School in a whyte district. She had to walk through a segregated neighborhood every day, enduring taunts, epithets, and rocks thrown her way. She excelled in English and history; an English teacher recognized her flair and urged her to write essays and stories, and even to submit one story to a magazine. It was published, as were other pieces in the school newspaper, but at this point, Payne’s ambition was to become a lawyer, “…just as I was so fierce about protecting my brother, I had a strong, strong, deeply embedded hatred of bullies…. So I said, ‘Well, I want to grow up and be a lawyer, and I want to defend the rights of the poor people.'” Due to financial constraints, she attended Crane Junior College briefly, and then a division of Garrett Biblical Institute. Her application to the University of Chicago Law School was refused, partly due to racial discrimination.

Payne worked as a matron in a girls’ reform school and as a Chicago Public Library clerk, during which time she became active in local civil rights affairs and was appointed by the Governor of Illinois to serve on the state’s Human Rights Commission. She then responded to a Red Cross advertisement to serve American forces in post-war Japan.

In 1948, Payne began her journalism career rather unexpectedly while working as a hostess at an Army Special Services club in Japan. She allowed a visiting reporter from the Chicago Defender to read her journal, which detailed her own experiences as well as those of African-American soldiers. Impressed, the reporter took the journal back to Chicago, and soon Payne’s observations were being used by the Defender, an African-American newspaper with a national readership, as the basis for front-page stories.

In the early 1950s, Payne moved back to Chicago to work full-time for the Defender. After working there for two years, she took over the paper’s one-person bureau in Washington, D.C. In addition to national assignments, Payne was afforded the opportunity to cover stories overseas, becoming the first African-American woman to focus on international news coverage; beginning with her coverage of the Asian-African Conference in Indonesia in 1955. Payne journeyed with then Vice-President Richard Nixon to the independence ceremonies for the African nation of Ghana in 1957, and covered other wars, events, and revolutions in countries such as Zaire, Senegal, and Nigeria. In 1966 and 1967, she reported first hand on African American troops in Vietnam. She accompanied Secretary of State Henry Kissinger on a six-nation tour of Africa in 1976.

During Payne’s career, she covered several key events in the civil rights movement, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott and desegregation at the University of Alabama in 1956, as well as the 1963 March on Washington. At the 1956 Bandung conference in Indonesia she was the only Black correspondent.

Payne earned a reputation as an aggressive journalist who asked tough questions. As one of only three accredited African Americans in the White House press corps, she once asked President Dwight D. Eisenhower when he planned to ban segregation in interstate travel. The President’s angry response that he refused to support special interests made headlines and helped push civil rights issues to the forefront of national debate.

Ethel Payne in Shanghai in 1973. Credit Library of Congress

In 1972 she became the first African-American woman radio and television commentator on a national network, working on CBS’s program Spectrum from 1972 to 1978, and after that with Matters of Opinion until 1982. In the early 1980s she was an advocate for the release of Nelson Mandela, the South African leader, from his internment in prison, and campaigned actively on his behalf. After leaving the Defender, she began writing a nationally syndicated column that continued until her death, while traveling to Africa to participate in anti-apartheid demonstrations and to tour refugee camps in Somalia, Sudan, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Payne died of a heart attack in 1991 at the age of 79.

Payne saw herself both as an emissary from and a representative of a large group of Americans long neglected by the mainstream media. A few years before her death, she told an interviewer, “I stick to my firm, unshakeable belief that the black press is an advocacy press, and that I, as a part of that press, can’t afford the luxury of being unbiased . . . when it come to issues that really affect my people, and I plead guilty, because I think that I am an instrument of change.”

Her innumerable honors include a 1967 award from the Capital Press Club for her Vietnam reporting; the Africare Distinguished Service Award, bestowed in 1983; and in 1987 the TransAfrica African Freedom Award. Several of Ethel Payne’s belongings and awards are on view at the Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C.

Source:

http://blackhistorynow.com-ethel-l-payne/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethel_L._Payne

https://www.washingtonpost.com-opinions-ethel-paynefirst-lady-of-the-black-pressasked-questions-no-one-else-would/2011/08/02/gIQAJloFBJ_story.html