“I had to work against all the odds to succeed, but succeed I did.”

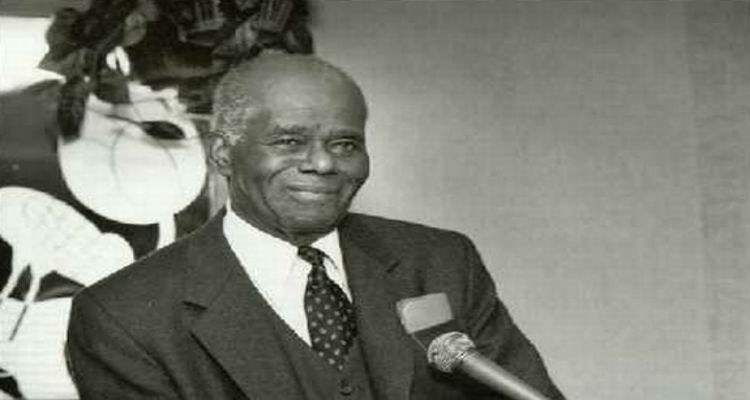

Dr. John Henrik Clarke was a Pan-Africanist scholar and historian and a pioneer in the creation of Africana studies, who became a professor emeritus at Hunter College without a high school diploma, or a Ph.D.

Dr. Clarke lived up to his name as a child, “little Fess,” (Little Professor) to become the Professor of African World History and in 1969 founding chairman of the Department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College of the City University of New York. Dr. Clarke was most known and highly regarded for his lifelong devotion to studying and documenting the histories and contributions of African peoples in Africa and the diaspora. He devoted himself to placing people of African ancestry “on the map of human geography.” In 1968 along with the Black Caucus of the African Studies Association, he founded the African Heritage Studies Association. In 1995 he received the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History’s highest award, the Carter G. Woodson Medallion.

Dr. Clarke was born John Henry Clark on January 1, 1915, in Union Springs, Alabama, the youngest child of sharecroppers John (Doctor) and Willie Ella (Mays) Clark. When he was four years old, the family farm was severely damaged by a storm, and Clarke’s father decided to move the family to Columbus, Georgia. Clarke’s mother died when he was seven years old, and his father supported the family by working as a farmer, as well as a fire tender at the brickyards. Clarke later recalled, “my father was a brooding, landless sharecropper, always wanting to own his own land….Ultimately the pursuit of this dream killed him.”

He also stated, “I was born into a family that was extremely poor, into a family that was separated by the search for work a great deal of the time, and into a family where the only book in the house was the bible, and where the beginning of my reading awareness was around the church and the Sunday School. Yet my awareness of Africa, began very early in my life.”

His great grandmother, Mary, exerted a powerful influence on his African consciousness by planting the word Africa in his mind, from a young age through the stories she would relate to him.

“One story she kept telling me repeatedly was the story of her first husband who was sold to a slave breeding farm in Virginia. After Emancipation she went into Virginia and spent three years looking for him. She said he was brave like in Africa. He stood up, he fought back. He was a man. He was so brave and so strong they sold him so he could breed other Africans to be brave and strong. Or at least, strong because no one breeds an Atlantian (enslaved black) to be brave.”

In Columbus, Clarke attended elementary and secondary school, becoming the first in a family of nine children to learn to read. In his fifth grade Dr. Clarke met “a great teacher,” Miss Taylor, who told him:

“I believe in you. I have confidence in you. I believe you’ll make it.”

Clarke had begun teaching Sunday school when he was just nine-years-old, and would read the Bible to elderly ladies in the community. During this time, he began to formulate the questions that would occupy him for all of his academic careers. “Reading the description of Christ as swarthy and with hair like sheep’s wool, I wondered why the church depicted him as blond and blue-eyed. I looked up the map of Africa and I knew Moses had been born in Africa. How did Moses become so whyte? I began to wonder how we had become lost from the commentary of world history.”

In addition to attending school, Clarke did odd jobs for various whyte families in the area. Interested in finding out more about African history, he asked a lawyer for whom he worked—and who had often lent Clarke books from his library—if he could borrow a book on African history.

“I went to a whyte man, Gagsteider, a lawyer, who had a good library. I had been taking the books from the library. He hadn’t missed them so I stopped bringing them back. I asked for a book on ancient history, and as we say in the South he let me down slow. He said very kindly, ‘John, I’m sorry but you came from a race of people who have no history. if you persevere, keep clean and work hard, and obey, you might make history one day.’ Then he prophesized for me the greatest thing a whyte man could prophesy for a Black man in the days when I was growing up: ‘One day you might be a great Negro like Booker T. Washington.’ I didn’t know anything about Booker T. Washington then and twenty years would pass before I could check him out. I didn’t even know it was supposed to be a compliment until later on.”

One day Dr. Clarke met a man who had a book called The New Negro. He opened it to an essay entitled: “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” by Arthur Schomburg, a Puerto Rican of African descent, and for the first time, “I knew that we not only had an ancient history, but we are an old people; and that we were already old before Europe was born–that half of human history was over before we knew that Europeans were in the world. That we had built great civilizations that not only had no jail system, they had no word in their language that meant jail. I was beginning to develop some security, I was beginning to look at whyte people with smugness: ‘Young things, you just got here…we’ve been here a long time.’ Then I began to understand that slavery was something that touched the life of all people on earth, and the period of our enslavement was short in comparison to the period when Europeans enslaved Europeans… I began to study slavery as an entity in human history.”

Despite Clarke’s demonstrated academic ability and a strong desire to learn, he was forced to drop out of school in the eighth grade in order to help support his family. As a teenager, he held a series of menial jobs, including working as a caddy for Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley, and other officers at Fort Benning, Georgia.

In 1933, at the age of 18, Clarke hopped a freight train to New York. He made the decision to move north for two reasons: partly because he had heard about the literary and cultural fervor of the Harlem Renaissance, and wanted to join it; and partly because he was frustrated at his inability to check out books from the segregated public library in his hometown. Clarke settled in Harlem, supporting himself with a series of low-paying jobs. He joined the Harlem History Club and the Harlem Writers Guild. In the Harlem History Club, he met Arthur A. Schomburg, Willis N. Higgins, and John G. Jackson, who became his mentors in reclaiming the African past.

Dr. Clarke described Arthur Schomburg as “kind of a handsome man, very imposing.” Schomburg told him, ‘Son, go study the history of Europe. If you understand the history of Europe you will understand how you got left out of history, who left you out and why you got left out of history. You will understand something else; that no oppressor can successfully oppress a consciously historical people because a consciously historical people would not let it happen. It became a necessity to remove you from history in order to convince you, at least in part, that you are supposed to be oppressed. And to remove from your eyesight every image of endearment, everything that endears you to yourself, so you can feel that at least in part, God has frowned on you and deserted you and put you outside the basis of humanity.’

Dr. Clarke began to study European history. His study took him to libraries, museums, attics, archives and collections in Asia, the Caribbean, Europe, Latin America and Africa. Through his association with members of the Harlem History Club as well as Josef ben Jochannan, William Leo Hansberry, Richard B. Moore, and J.A. Rogers, Dr. Clarke learned much about black history. He developed as a prolific writer and lecturer. His first published work was a collection of poetry. He wrote more than fifty short stories, the most famous being The Boy Who Painted Christ Black. In addition, he wrote 6 books, edited and contributed to 17 others, as well as a number of articles and pamphlets.

From 1941 to 1945, Clarke served as a non-commissioned officer in the United States Army Air Forces, stationed in San Antonio, Texas, ultimately attaining the rank of master sergeant. Afterward, he returned to New York and his research. Although Clarke took classes at New York University—where he studied history, world literature, and creative writing—and Columbia University, he did not earn a degree from either institution. However, he co-founded the Harlem Quarterly (1949–51), and worked as a book review editor of the Negro History Bulletin (1948–52), an associate editor of the magazine, Freedomways, and a feature writer for the black-owned Pittsburgh Courier.

During the 1940s, Clarke began teaching African and African American history in community centers in Harlem. “At first I was an exceptionally poor teacher. I was nervous, overanxious, and impatient with my students. I had to acquire patience with young people who giggled when they were told about African kings. I had to understand that these young people had been so brainwashed by our society that they could see themselves only as depressed beings.”

Clarke taught at the New School for Social Research from 1956 to 1958. Traveling in West Africa in 1958–59, he met Kwame Nkrumah, whom he had mentored as a student in the US, and was offered a job working as a journalist for the Ghana Evening News. He also lectured at the University of Ghana and elsewhere in Africa, including in Nigeria at the University of Ibadan.

During the Black Power movement in the 1960s, Clarke advocated for studies on the African-American experience and the place of Africans in world history. He challenged the views of academic historians, which sparked controversy, and helped shift the way African history was studied and taught. ‘If some of the scholarships he championed was dismissed by traditional historians as specious propaganda seeking to aggrandize African influence on Western culture, Mr. Clarke threw the charge right back, accusing white scholars of having disguised their own Eurocentric propaganda as historic fact.’ One such controversy erupted over the book William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Scholars Respond, which was edited by Clarke and published in 1968. Clarke and the other contributors accused Styron of painting a false picture of slavery and of Turner’s character in the novel, The Confessions of Nat Turner. Even as Clarke generated controversy, though, his views gained coverage in the mainstream media. The same year, Clarke served as a consultant and coordinator of the CBS television series, “Black Heritage: The History of Afro-Americans.”

Clarke eventually earned a license to teach African and African American history in New York from People’s College in Málveme, Long Island. In 1964, after more than 20 years of teaching in Harlem community centers, Clarke landed his first regular school assignment: Director of the Heritage Teaching Program for the Harlem Youth-Associated Community Teams (Haryou-Act), an anti-poverty agency. He also taught African and African American history at New York University’s Head Start Training Program.

In 1969, Clarke joined the faculty of Hunter College, City University of New York, where he established the department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies. While he was teaching at Hunter College in New York and at Cornell University in the 1980’s, Clarke’s lesson plans became well known for their thoroughness. They are so filled with references and details that the Schomburg Library in Harlem asked for copies. Clarke decided to provide them, because, “…50 years from now, when people have a hard time locating my grave, they won’t have a hard time locating my lessons.” Dr. Clarke, largely self-taught and highly outspoken, became an imposing figure in Black intellectual circles.

Even after he retired from Hunter in 1985, Clarke continued to travel and deliver lectures all over the world. Several of these lectures were later collected and published; these included New Dimensions in African History: The London Lectures of Dr. Yosef ben-Jochannan and Dr. John Henrik Clarke and African People in World History.

Clarke also continued to generate controversy. In 1993, responding to the 1992 celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World, Clarke published the book Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust: Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism. In the book, he wrote “Christopher Columbus had helped to set in motion the Atlantic slave trade, the single greatest holocaust in human history,” Clarke claimed. Instead of a day of celebration, he suggested, Columbus Day should become “a justifiable day of mourning for the millions of Africans and so-called ‘Indians’ who died to accommodate the spread of European control over the Americas and Caribbean Islands.”

With regards to his personal life, Clarke’s first marriage was to the mother of his daughter Lillie (who eventually pre-deceased her father). In 1961, Clarke married Eugenia Evans in New York, and together they had a son and daughter: Nzingha Marie and Sonni Kojo. The marriage ended in divorce. In 1997, John Henrik Clarke married his longtime companion, Sybil Williams.

Dr. Clarke died of a heart attack on July 12, 1998, at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center. He was buried in Green Acres Cemetery, Columbus, Georgia. ‘If it is unusual to become a full college professor without benefit of a high school diploma, let alone a PhD, nobody said Professor Clarke wasn’t an academic original,’ Robert McG. Thomas Jr. wrote in Clarke’s obituary in the New York Times.

Dr. Clarke is often quoted as stating that “History is not everything, but it is a starting point. History is a clock that people use to tell their political and cultural time of day. It is a compass they use to find themselves on the map of human geography. It tells them where they are, but more importantly, what they must be.”

Articles Dr. John Henrik Clarke

Why Africana History?, by John Henrik Clarke

The Concept of Deity, by John Henrik Clarke

A Great and Mighty Walk, by John Henrik Clarke

The Impact of Marcus Garvey, by John Henrik Clarke

Source:

My Life in Search of Africa by John Henrik Clarke

http://africana.library.cornell.edu/africana/clarke/index.html

http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/afprl/clarke/dr.-john-henrik-clarke201420th-century-griot-by-dr.-marimba-anni

https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-55842343/in-memoriam-dr-john-henrik-clarke-1915-1998

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/John_Henrik_Clarke.aspx