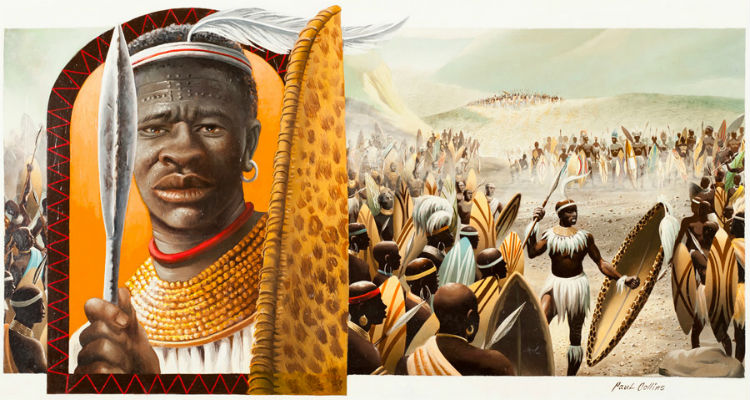

“There have been many outstanding leaders and generals in the African continent, but none captures the imagination as Shaka of Senzangakhona. From a small volunteer army of approximately 200 and a territory that seemed, in comparison with other neighboring states, no more than a small, local district, Shaka built in a period of ten years a formidable standing army of about 60,000 to 70,000 highly trained men. His rule extended for a large part of Southern Africa… Shaka was a consummate leader. Not only was he a great military genius, but his varied gifts demonstrated qualities of organization and innovation that was unique. The military machinery he initiated brought about, fifty years later, one of the most dramatic defeats the British army suffered in all its colonial history.”

In the early nineteenth century, Shaka Zulu, emerged as a leading figure in the military and political state of affairs in the Zulu Kingdom of southern Africa. He was born out of wedlock to a father who was the Ruler of the Zulus. His clan exiled him at a young age. However, upon his father’s death, he returned to claim his place as the King. As a ruler, he focused on building a mighty army, and subsequently conquered and united several nations to form a powerful Zulu Kingdom. He placed emphasis on military organization and skills. Military innovations such as the assegai (Zulu thrusting spear) and the impondo zankomo “bullhorn” attack formation enabled Shaka’s army to surround and annihilate his enemies. His military reforms enabled, the Zulus to be victorious in each of their battles against other nations.

Shaka was born in 1786. His father, Senzangakona, was the Zulu King. According to Zulu lore, his father ‘came upon his mother, Nandi, while she was bathing in a woodland pool and fired by her beauty, he boldly asked for the privilege of ama hlay endlela.’ She consented and three months later she was pregnant. As soon as her pregnancy was discovered, a messenger was rushed off to bring a formal indictment against Senzangakona. However, the elder of the Senzangakona’s people denied the charge stating, “Impossible. Go back home and inform them the girl is but harbouring I-Shaka (an intestinal beetle thought to cause interruption of menstruation).” However, when Nandi gave birth, her people sent a message back stating, “There is your beetle. Come and fetch it for it is yours.” Reluctantly, they came and Nandi was made the third wife of Senzangakona. The baby was given the name U-Shaka.

It is said that Shaka’s first six years were overshadowed by the unhappiness of his mother, whom he adored. One day while sheep herding, in a moment of negligence, he allowed a dog to kill a sheep. His father became angry and because his mother defended him, they were turned out of Senzangakona’s kraal.

Shaka became a herd boy at his mother’s I-Nguga kraal, twenty miles away from his father’s. He was subjected to bullying. The children of the Langeni, his mother’s people, used to tease him about his crinkly ear and his short and stumpy phallus. His mother would soothe him by telling him, “Never mind, my Um-Lilwane (Little Fire), you have got the isibindi (liver, meaning courage) of a lion, and one day you will be the greatest ruler in the land. I can see it in your eyes. When you are angry they shine like the sun, and yet no eyes can be more tender when you speak comforting words to me in my misery.”

When Shaka was old enough to wear a loincloth he was put in his father’s charge. He went through the ceremonial rites of puberty. But when his Royal father presented him with his umustsha (ceremonial loincloth), he rejected it with disdain. He was eventually expelled from the kingdom and sent back to his mother.

It is said that Shaka had a very definite reason for deciding to continue living unclothed. He wished it to be known that he was now physically adequate. In particular, he wanted the Langeni people to see and know this, and especially his former tormentors, who would now be envious of him.

Nandi took Shaka to live with her aunt, in Mtetwa-land, near the coast. Ngomane, the headman of the district in which they settled treated Nandi and Shaka with a kindness that Shaka never forgot. The ruler of the Mtetwa people was Jobe. His sons had conspired against him. One had been put to death and the other, Godongwana had fled. He changed his name to Dingiswayo (The Wanderer). When Jobe died, Dingiswayo returned and became the ruler. He revived the Izi-cwe regiment by calling up Shaka’s age group. Thus Shaka became a soldier.

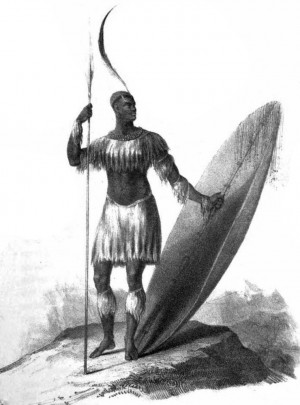

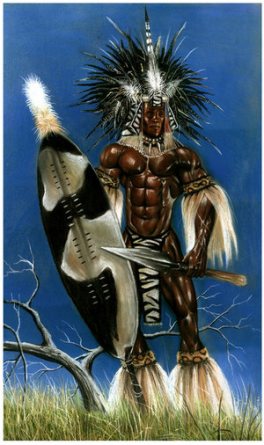

Shaka grew up to be a skilled warrior of great strength. His regiment did not fail to note his prowess as a warrior and he was allowed to lead the giya (victory dance). Shaka’s outstanding deeds of courage would see him rise as one of Dinigiswayo’s foremost commanders. He was given the name, Nodumehlezi (the one who when seated causes the earth to rumble). He was the tallest man in the army, standing well over six feet. He was broad-shouldered, slim-waisted, and his frame was svelte and elegantly knit. In strength and daring he had no equal. In combats of wrestling and other matches, he would take on two of the strongest rivals at a time and beat them both. He was also the best and most graceful dancer. He became the idol of his people. One of Shaka’s most talked-about exploits at this time was combat with a huge madman who was terrorizing the district. He had robbed and killed a number of people, and when several soldiers were sent to take him into custody, he beat them off. Shaka attacked him singlehandedly and in a terrific fight killed him.

Even his father who had once cast him off, became one of his greatest admirers. The latter on a visit to Dingiswayo, was honoured by a traditional dance, and seeing one of the warriors, whose fire and grace excelled all the others asked who he was. When told that it was his own son he was so delighted that he called him over and named him his heir despite the fact that he was not born of a union with one of his own wives.

Shaka was twenty-six when his father died. Another son, Sijuana, took his father’s place, but Dingiswayo gave Shaka the military support necessary to oust and assassinate his senior brother, and make himself ruler of the Zulu, although he remained a vassal of Dingiswayo. When another half-brother, Dingaan, came for the throne, Shaka merely laughed at him and told him to go on his way. Later Dingaan was to become a powerful ruler and Shaka was to regret that he had only laughed.

When Shaka took over the rulership of the Zulu, they were an insignificant people owning less than 100 square miles of land, that he could reach any of its confines within an hour. Finding out that they had no army, he called up every Zulu man capable of bearing arms. His first step was to segregate all married men between the ages of thirty and forty. He built a separate kraal for them which he called “Belebele,” meaning Everlasting Plague. Shaka hated married men. Next, he segregated the youths between seventeen and twenty, informing them that they were to remain bachelors. He subjected them to fierce discipline. Leading by example, Shaka once sat down on a hornet’s nest, scooped out the angry insects, and beat them off without raising. He wanted strong men only. He trained his warriors well and toughened them to jog over hills for up to 50 miles in a day without shoes.

An English traveler who knew Shaka well, said of these warriors, “Their figures are the noblest that my eye has ever gazed upon; their movements the most graceful; and their attitude the proudest—standing like forms of monumental bronze. They hailed Shaka by stating: ‘You mountain, you lion, you elephant, you that are Black.’”

Shaka revolutionized military tactics. At the time it was the custom for an African warrior in battle to throw the assegai — a long pole weapon made of wood with pointed iron at the end and thrown like a javelin — and immediately advance or retreat according to the action of the enemy. Shaka considered this fighting method ineffective, and cowardly. Tired of the assegai, Shaka introduced the ikwla, a weapon with a shorter sphere and a longer spearhead; and convinced his unit of the effectiveness of close combat rather than spear-throwing. This weapon gave Shaka’s warriors a huge advantage over opponents when they came up close for hand-to-hand combat. Two heroes took immediately to his ideas, Mgobhozi of the Msane and Nqoboka of the Sokhulu. They were to be his lifelong comrades.

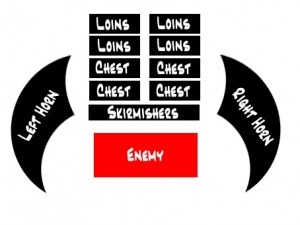

Shaka supposedly introduced cowhide shields, which were much stronger than the iron or wood shields used previously. He also changed the attack formation, modeling it after the shape of a bull’s horns. This was a three-part attack system in which seasoned warriors formed the “chest” of the horn at the front, pinning the enemy into a position where it could be easily attacked. Younger warriors would form the “horns” and encircle the enemy, attacking from the sides, and additional warriors formed the “loins,” standing behind the “chest” with their back to the battle, protecting against any additional attackers. He also had warriors carry different colored or patterned shields, depending on their rank. In a troop of hundreds, this made it much easier for the warriors to know exactly where to go when forming the bullhorn.

Shaka was concerned not only with the efficiency of military techniques but also with the consolidation of political authority. He saw the creation of a strong and efficient army as a means of establishing order and eliminating the rampant banditry of states and individual groups. He also took several precautions to consolidate his power by eliminating many of his relatives who could try to usurp his position, before setting out to settle old scores with the Langeni, who had been cruel to him when he was a boy. After surrounding them, he called for all the people to be brought before him. He singled out all those who had humiliated him and his mother and told them that they would all die: “This is the death I have in mind for you. The slayers will sharpen the projecting upright poles in this cattle-kraal–one for each of you. They will then lead you there, and four of them will you up singly and impale you on each of the sharpened poles. There you will stay till you die, and your bodies, or what will be left of them by the birds, will stay there as a testimony to all, what punishment awaits those who slander me and my mother.”

His next objective was Panagashe, ruler of the Butelizi. When the two forces met, the Butelizi, confident in their old way of victory, threw their spears. But to their amazement, Shaka’s warriors caught the weapons on their shields, flung the spears back, and charged down on them with blood-curdling yells. Soon the Butelizi were on a headlong flight. Shaka took all their cattle and gave the young captive warriors the option of joining his army or death. His men then slaughtered the rest, except the young wives and virgins. As to Pangashe, he left him to die a slow death sitting upright on a sharp stake.

After wiping out several other smaller nations, Shaka set out against Matwane, chief of the Ngwanemi, who was held to be invincible. When Matwane learned of Shaka’s plan, he marched off to ally himself with Zwide, King of the Ndwande.

After Dingiswayo, Zwide was the most powerful king in South Africa, and he too thirsted for supreme power. He welcomed Matwane and the two hatched a plan to eliminate Dingiswayo. Instead of attacking him openly, they enticed him into a hut and chopped off his head. Taking out his heart, liver, and other vital organs, Zwide boiled them and drained off the fat for a charm.

Shaka was beside himself over Dingiswayo’s death and annexed the whole nation after killing the ruler who had succeeded Dingiswayo.

Zwide, now ready, marched to meet Shaka. Fearing that the powerful Ngwanes might join Zwides forces, Shaka attacked them, massacring some 30,000 of them. While in the vicinity, he annihilated the Tembas. Zwide on the march, induced other rulers to join him but this did not help. The two finally met on the banks of the Mhlatuze River and a battle fought until the river ran red with blood and corpses piled deep. It was Zwide who withdrew, and headed once again for Zululand. On the march to meet him, Shaka laid waste all the land over which Zwide would pass and then withdrew. Zwide, who had left his base with only a day’s ration in the expectation that he could forage cattle and food on the way, found himself without food. After four days, when Zwide’s men were worn out from hunger, Shaka sent out his young blood to attack them achieving another great victory.

The last obstacle in the way of his goal of achieving supremacy in South Africa was the still unsubjected territory of Zwide’s people, Ndwande. With an army of 30,000, Shaka set out for Ndwandeland. As he approach, Zwide’s people, some 40,000 men, women and children, sought refuge in the mountains. With Shaka hot in pursuit, they made a stand on the plateau of a snow-covered mountain. The Zulus, coming within a few feet of Nwadnes halted. A dramatic silence ensured while each warrior steeled himself for the coming conflict. Then Shaka, gave the signal. When it was over every single Ndwande had been tossed from the cliffs.

After this massacre, Shaka’s nearest enemy was at least 600 miles away. Some nations, fearing him had fled further. By 1820, four years after he started out on his first campaign, and at the age of thirty-four, Shaka had conquered a territory larger than France. A ring of desert land and a devastated area protected it from invasion. His people had become immensely wealthy. His warriors saluted him, “Bayede!” the equivalent of “Hail Caesar!” Then to clashing swords, they would chant:

“Thou has scattered all the nations

What remains now for thy forces to fight?

Oh, what remains now for thy forces to fight?”

Shaka now had a magnificent army, restless for battle, but with no one to fight. To get rid of the surplus, he would incite one regiment to attack another. With no outside enemies on which to fix their hate, his people began fighting among themselves. To preserve order he kept executioners by his side.

Defiance increased, however.

Once when he was dancing, someone struck at his heart with a dagger but he succeeded only in wounding his arm. Thousands were put to death in retaliation. His mother sought in vain to stem the slaughter, and when she died, some 7000 people were put to death. Shaka wept, and all whose eyes were dry, or who did not come to the royal city to mourn, were executed. It is said that pregnant women and their husbands from his people were murdered, and crop planting and milk production were banned. However, one Zulu member stood up to Shaka and reminded him that his mother was not the first person to ever die in their community and that some of his mourning methods were too harsh. Shaka listened, called off his mourning measures, and rewarded the tribe member for bravery in speaking up.

Nine years of his dictatorship filled people with desperation and they longed for his death. Dingaan his half-brother resolved to kill him at all costs. Plotting together with one of Shaka’s domestics name Satam, Dingaan and his brother crept into Shaka’s hut and stabbed him as he sat before the fire. They plunged the dagger into him again and again. Before, he died, Shaka said: “What have I done to you! Oh, children of my father.”

Shaka’s body was flung into a corn pit where it was left to the vultures.

Controversial as he was, Shaka had left a powerful legacy. By sheer strength of character and visionary ideas, he organized his people, making them into a fighting force. He made it difficult for European men to seize their lands. His disciplined training gave the Zulu the finest physique in the world. Years later when the English wanted to conquer the Zulus, they demanded that Zulu youths be permitted to marry.

Shaka Zulu is the inspiration for a song used throughout Africa when a revered authoritative figure is celebrated. The opening lines are, “He is Shaka the unshakeable, Thunderer-while-sitting, son of Menzi. He is the bird that preys on other birds.”

Photo credit:

2nd image in the post – Shaka Zulu by tariq12

Source:

World’s Great Men of Color: Vol 1 by J.A. RogersShaka Zulu: Black Napoleon by E. A. Ritter

Emperor Shaka the Great (epic poem) by Mazisi Kunene

http://afkinsider.com/57305/16-things-made-shaka-zulu-a-military-genius/

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/king-shaka-zulu