Windradyne (c.1800-1829), the Indigenous Australian resistance leader, was a northern Wiradjuri man of the upper Macquarie River region in central-western New South Wales.

Windradyne’s date of birth is unknown, but on his death in 1829 his obituary in the The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser—thought to be by his settler friend George Suttor from ‘Brucedale Station’ north of Bathurst—stated “His age did not, I think, exceed 30 years” thus putting his year of birth at approximately 1800.

Coe’s biography of Windradyne from 1989 states that he was handsome and well built, with broad shoulders and muscular limbs. He had dark brown skin, thick black curly hair, and a long beard. He typically wore a headband, and had his beard plaited into three sections.However, Coe’s description does not fully correlate with a drawing of a Wiradjuri warrior that is thought to depict Windradyne.

When Windradyne visited Parramatta to meet with Governor Thomas Brisbane in December 1824, the Sydney Gazette (using the British appellation for him of Saturday) wrote that:

“He is one of the finest looking natives we have seen in this part of the country. He is not particularly tall, but is much stouter and more proportionably [sic] limbed than the majority of his countrymen; which, combined with a noble looking countenance, and piercing eye, are calculated to impress the beholder with other than disagreeable feelings towards a character who has been so much dreaded by the Bathurst settler. Saturday is, without doubt, the most manly black native we have ever beheld—a fact pretty generally acknowledged by the numbers that saw him…”

The Wiradjuri Buudhang (People) are an ancient people. It has been forgotten when they first settled in the inner parts of New South Wales. Archaeological evidence suggests, though, that the Wiradjuri have occupied their lands, equivalent to about a quarter of New South Wales or about the size of England, for at least 10 000 years. Many, furthermore, have argued that the Wiradjuri have been there for much longer with that, with estimates of between 15 000 to 30 000 years. Needless to say, from the point of view of the Wiradjuri, their territory has always been theirs since the Dreamtime.

Like other indigenous Peoples, the Wiradjuri shared many similar beliefs & customs. To the ignorant, which meant the entire population of the British colony at Sydney, the Wiradjuri appeared to be no different than other Indigenous peoples which they had encountered around Sydney. There were, however, fundamental differences & these would come into play as the British pushed inland. Although these differences are numerous, probably the most important was the population size of the Wiradjuri People. Even though the Indigenous population was unknown in the early 1800s, it has been somewhat accepted that 3.3 million Indigenous Peoples inhabited Australia. Out of this number, at least 500 000 were Wiradjuri. Whatever the real number, though, it can be said with certainty that the Wiradjuri People were the largest nation in Australia at that time, including the British colonials.

Another important aspect to Wiradjuri society were the warriors. All men, especially the young, were expected to be able fighters. Why this is the case, no one seems to understand. The Wiradjuri, for the most part, were a peaceful people & had no conflicts with their neighbours. Nonetheless, a warrior tradition, although not central to Wiradjuri culture, was an important part. It is argued by many scholars in the field that the Wiradjuri “warrior” was essentially a hunter. The difference in Wiradjuri society was not really considered as distinct, unlike in European societies. The Wiradjuri ability to hunt, was easily & skilfully transferred into soldiery.

It did not take long for trouble to start in Bathurst. Until 1821, the outpost at Bathurst had hardly grown. It continued to be nothing more than a small town which had a small army garrison of the 39th Regiment, a handful of public servants, & a few private citizens. Even after Brisbane reversed Macquarie’s policies on territorial expansion, Bathurst’s population never got beyond 100. But in 1821, what with government incentives for colonists to settle in the Bathurst region, a few hundred decided to accept the government’s offer.

Still this did not worry the Wiradjuri overly much. However, as the numbers grew and it became evident that the acquisition of land was the main intent of the British, the attitude of many Wiradjuri began to change. The main instigator among the Wiradjuri at the beginning was the elder Windradyne. Very early in the piece, Windradyne questioned the position which the older Wiradjuri elders had adopted. Although he was not at Macquarie’s meeting in 1916, and thus did not participate in the original informal agreement, he nonetheless accepted this agreement with Macquarie.

Now things had changed and he was the first of the Wiradjuri to notice it. The Wiradjuri leadership, however, refused to accept Windradyne arguments & continued to stick to their agreement with Macquarie. As such, more & more colonists arrived to begin claiming ownership of land in order to commence farming. Naturally the Wiradjuri had no concept of private ownership of land & tensions began to rise between the two groups. Soon, as was bound to happen, altercations took place.

Windradyne, hearing that some colonists had begun acts of violence against fellow Wiradjuri, began to see for himself what was happening. With a small band of fellow warriors, Windradyne’s group swept through the Bathurst region gaining intelligence. He noted two things. First, the older colonists who had been in the district for some time continued to have cordial relations with Wiradjuri & never challenged them. The recent arrivals, however, refused access to the land & were prepared to use violence when their demands were not followed. These were declared by Windradyne to be Wandang (bad spirits).

Windradyne decided upon a campaign of intimidation against the Wandang. The colonists who had accepted Wiradjuri customs would be left in peace. Having said that, it was never Windradyne’s intention to kill anyone. He knew that the colonists had powerful weapons. Instead, he wanted to either make the Wandang accept Wiradjuri ways, especially in regards to the land, or make them leave Wiradjuri territory. Alas the Wandang did not see things this way.

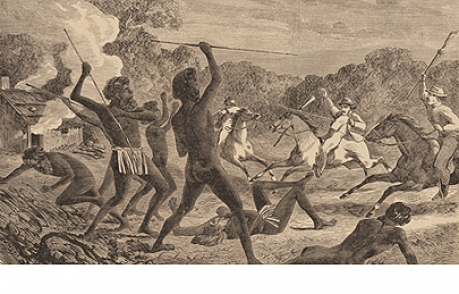

It did not take long before small scale skirmishes took place. At this point, this involved only about ten Wiradjuri, including Windradyne, & one or two Wandang. The Wiradjuri seldom attacked beyond chasing the Wandang off of the farm which they had established. Yet this very process itself meant that the ejected colonial settlers arrived at Bathurst with tall stories of escaping massive native attacks. As these escapees grew in number, Commandant Morrisett, the man in charge of Bathurst, began to send patrols out to confirm the stories of native rebellion.

The Wiradjuri began to strike back and conflict escalated as stations were attacked and cattle speared. Lives were lost on both sides. Whyte settler reports in the Sydney Gazette record over 13 stock keepers killed by mid-1824. There are no records of the Wiradjuri men, women and children killed in reported retaliatory attacks and poisoning. Wiradjuri resistance to the settlement also intensified with the strength and stature of one leader Windradyne (Saturday) becoming legendary.

In December 1823 Windradyne was put in irons for a month by the commandant of Bathurst, Major Morissett, for killing two bullocks.

“One of the chiefs, (named Saturday) of a desperate tribe, took six men to secure him and they had actually to break a musket over his body before he yielded, which he did at length with broken ribs…”

As conflict came closer to the fledgling town another report describes the shooting of Windradyne’s family by a farmer on the potato fields on the banks of the Macquarie, across from the early settlement. Windradyne survived this encounter and in May 1824 mounted a campaign of guerrilla warfare, with attaches on several stations in the Bathurst area.

Early settler, William Suttor, described his narrow escape from the inflamed warriors, thanks to the lasting friendship he had established with the Wiradjuri. When they arrived at this jut he was able to speak with Windradyne in Wiradjuri and saved himself and his family. Attacks were recorded at Millah Murrah, The Mill Post and Warren Gunyah.

The killing of a Wiradjuri woman and two girls at Raineville near O’Connell in May 1824 led to the arrest of five stockmen. Prosecution of the case drew consternation from settlers who called for military intervention against the Wiradjuri. The accused were not convicted.

Governor Brisbane proclaimed Martial Law on 14 August 1824 and dispatched 75 soldiers to Bathurst with magistrates permitted to administer summary justice.

A reward of 500 acres (203.3 ha) was offered in reward for the capture of Windradyne. Official records of engagement and losses were scant but W.H. Suttor, one of the few settler advocates for the Wiradjuri, described their suffering at the hands of the forces assembled under Major Morisset.

“When martial law had run its course extermination is the word that most aptly describes the result. As the old Roman said, ‘they made a solitude and called it peace”.

Soldiers, mounted police, settlers and stockmen carried out numerous attacks on Indigenous people. The attack continued for two months but no record of casualties was kept. By October groups of Wiradjuri were being reported coming into Bathurst to surrender. Martial Law was repealed on 11 December, 1824.

Seventeen days later Windradyne led a group of Wiradjuri to Parramatta, where, with a dignity acknowledged by whyte observers, he made an entreaty for peace at the Governor’s Annual Feast. On the same day, the Colonial Secretary, Early Bathurst, sent a dispatch from England rebuking Governor Brisbane for providing insufficient justification for his declaration of martial law. Brisbane was later recalled to England.

Windradyne was reported to have been mortally wounded in a tribal fight on the Macquarie River, and to have died a few hours later on 21 March, 1829 at Bathurst hospital on the corner of Bentinck and Howick Streets. The Suttor family disputed earlier accounts of Windradyne’s death and burial, claiming that he had in fact departed from Bathurst hospital to join his people at nearby Brucedale, and that the died on the property in 1835. In 1954 the Bathurst District Historical Society erected a monument beside a Wiradjuri burial mound at Brucedale, attaching a bronze plaque commemorating.

Windradyne has become a character of national importance as a resistance hero. A suburb at Bathurst and a student accommodation village at Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, are named after him. Windradyne’s grave is listed on the State Heritage Register and is protected through a voluntary conservation order.

Sources:

http://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showthread.php?t=37043

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/windradyne-13251

http://heritagebathurst.com/history-matters/indigenous-history/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windradyne