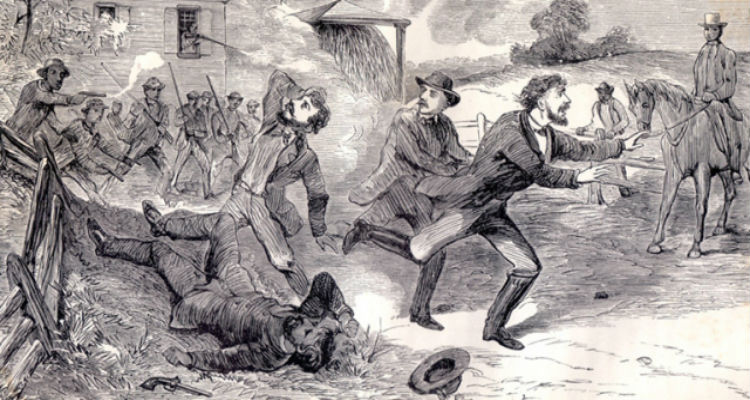

In 1851, in Christiana, Pennsylvania, one of the earliest armed confrontations took place between a group of African-Americans and Euro-American abolitionists and a Maryland posse intent on capturing four fugitives hidden in the town.

In February 1793, Congress passed the first fugitive law, requiring all states, including those that forbade the Maafa (Atlantic slavery), to forcibly return enslaved people who had escaped from other states to their original enslavers. The law stated that “no person held to service of labor in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.”

As Northern states abolished the Maafa, most relaxed enforcement of the 1793 law, and many passed laws ensuring fugitives a jury trial. Several Northern states even enacted measures prohibiting state officials from aiding in the capture of runaways or from jailing the fugitives. This disregard of the first fugitive law enraged Southern states and led to the passage of a second fugitive law as part of the “Compromise of 1850″ between North and South.

Immediately this law sparked outrage among abolitionists who viewed the law as further protection of the immoral institution of slavery. They vowed to engage in a form of civil disobedience; knowingly breaking the law that they felt was unjust. Open skirmishes began to take place between Southern slave catchers and Northern abolitionists, with armed altercations and confrontations taking place in a number of Northern communities between 1851 and 1861.

Maryland, a slave state bordered on Pennsylvania, a free state. The famous Mason-Dixon Line was drawn on their shared border as a delineation of north (freedom) and south (slavery.) Therefore, numerous fugitives from Maryland and other slave states made their way into the region, often assisted and protected by anti-slavery Quakers. In response, slaveholders or their representatives operated in the area with increasing frequency after 1850, kidnapping fugitives and returning them to the South.

One slave-capturing expedition in September, 1851 led to the Christiana Riot.

John Beard, Thomas Wilson, Alexander Scott, and Edward Thompson (the names they were known by in Pennsylvania) escaped enslavement of the Gorsuch family of Maryland and took up residence in Lancaster County. Under provisions of the 1850 fugitive law, the elder Gorsuch – a Methodist deacon, known as a wealthy kind enslaver – went to Philadelphia for the proper papers, along with his son, cousin, nephew, and two neighbors.

Joined by U.S. Marshal Henry Kline and two officers, Gorsuch and his party took the train to Christiana, after learning that the fugitives were on the farm of William Parker, a free African American.

Parker had lived in the Lancaster County region, since he ran off from the Maafa in Maryland in 1839 and had formed a vigilance group among local Blacks and Quaker neighbors in the early 1840s. In his story, published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1866, Parker stated that he had instigated riots to free fugitives from as early as 1841.

For example, one incident, probably from 1850, involved slave-catchers taking a woman named Elizabeth. They stopped at a tavern, which gave Parker and his people time to catch up to them and set a trap. One of Parker’s men, mounted on a conspicuous white horse, rode behind the wagon with the captured fugitive. This signaled the others, in hiding on Gap Hill, which wagon to attack. They did, the woman escaped, and Parker claimed the slave-catchers were so badly beaten that up to three of them later died. Parker also arranged the barn-burning of a tavernkeeper who had said he would welcome slave-catchers, and he and his associates attacked blacks they believed to be informers.

On September 11, 1851, Gorsuch and his men went to Parker’s house and told the fugitives they wouldn’t be punished if they returned with him peacefully. However, the African Americans on the second floor responded by hurling things at the men in the yard, injuring some of them. Kline then announced his official position and threatened to come upstairs. Gorsuch started up the stairs, but an axe and a pronged fish spear were thrown at him, so he retreated out of range. Kline read the warrant and both men then left the house into the yard. A shot was fired, but each side claimed the other had fired it.

A couple of hours passed. Parker said he engaged in a scriptural debate with Gorsuch. There were seven whytes against seven blacks, two of the latter women. Kline decided that there was no way to take the fugitives with the force on hand, and he advised leaving. But Gorsuch seemed to think time was on his side as some of the people in the house, including Parker’s brother and sister-in-law, wanted to give up.

However, a large number of local blacks, well armed as well as some whyte neighbors, arrived. The slave catching party was warned to leave quickly or blood would be shed. Kline seemed to find this a good idea, but Gorsuch moved toward the house. The African American resisted and Gorsuch was killed. Gorsuch’s son ran to his aid, but was badly wounded himself. The US Marshals and the other slave catchers retreated.

Later the Marshals returned with three detachments of US Marines. By that point, William Parker and his wife Eliza were already en route to Canada. Parker was hidden for a time in upstate New York by Frederick Douglass.

Thirty-eight other men, however, were arrested including four whyte Quakers. They were all charged with treason. Parker also left behind a large packet of letters from fugitives and resisters that would have incriminated many in the area had it come into the hands of the law, but a local Quaker found it first and burned it.

The first man brought to trial, the Quaker Castner Hanway—erroneously thought to be the leader of the anti-slavery men—was acquitted. Since authorities thought this was the strongest case, they released the other 37 men.

The acquittal of all of the defendants was hailed by Northern abolitionists as a major victory against slavery and especially against the Fugitive Act. Frederick Douglass viewed the resistance at Christiana as having a special moral and political significance because the event was evidence of Black strength.

Southerners, however, expressed anger and shock, and felt that their property could not be secured even in the North. Thus the riot became the first of a series of episodes including “Bleeding Kansas” in the late 1850s and John Brown’s Raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 that propelled the nation toward the Civil War.

Source:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-christiana-riot

http://www.etymonline.com/cw/christiana.htm

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/christiana-riot-first-open-resistance-fugitive-slave-law

http://www.umbc.edu/che/tahlessons/pdf/Slavery_and_Civil_Disobedience_Christiana_Riot_of_1851(PrinterFriendly).pdf