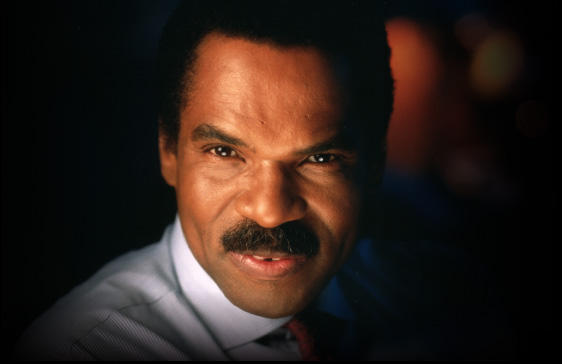

Reginald F. Lewis, the owner of TLC Beatrice International, a $500 million European conglomerate in food processing and distribution, was at one time the most prominent African-American businessman in America. His purchase of Beatrice International in 1987—a billion-dollar deal—was the largest offshore leveraged buyout in the history of American business.

Lewis was born on December 7, 1942, in Baltimore, Maryland into a middle-class family. His father was a postal worker and his mother a teacher. He once said that he began selling newspapers when he was 9 years old, earning about $20 a week and saving $18. Lewis’s parents separated when he was six, and he went to live with his maternal grandparents. The boy soon bonded with his grandfather, listening attentively to the older man’s war stories of France during World War I. After attending a Roman Catholic private school, Lewis went on to Dunbar High School, where he excelled both in his studies and in sports. He was a quarterback on the football team, a shortstop on the baseball team, and a forward on the basketball team. In all three sports, he was named captain. Meanwhile, he worked nights as a waiter in an exclusive country club. Jean S. Fugett, Lewis’s half-brother, and the current chief executive officer of TLC Beatrice, told the New York Times: “In those days, all [Reginald] ever did was work and play sports. He was always extremely industrious and never one for idle time.”

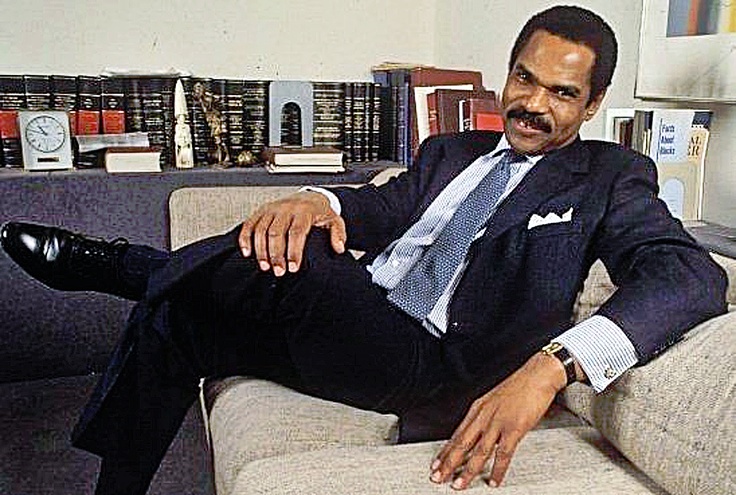

Lewis graduated from Virginia State University before entering Harvard Law School. After graduating in 1968, he joined the New York law firm of Paul Weiss Rifkin Wharton & Garrison. In the early 1970s, he opened his own law firm, Lewis & Clarkson, which specialized in venture capital projects.

The partners concentrated on Lewis’s strong suit: corporate law and the venture capital business. Much of the firm’s work was spurred by new federal legislation aimed at encouraging business opportunities for minorities. Lewis found himself helping clients such as General Foods and Aetna to launch programs intended to stimulate minority enterprises. He also quickly developed a reputation for venture capital development for minority-owned firms. According to Black Enterprise, “Over the years, Lewis…helped a large number of minority enterprise small business investment corporations (MESBICs) acquire funding and gained a great deal of practice in the art and science of structuring deals. As general counsel to the Washington, D.C.-based American Association of MESBICs …between 1972 and 1979, Lewis became recognized as an architect of the MESBIC industry.” It has been estimated that Lewis negotiated more than $100 million in transactions for MESBICs in the years between 1973 and 1984.

Working with venture capital companies in that capacity served as a training ground for Lewis. It was only a matter of time before the enterprising attorney decided to do some deals for himself. In 1983 he formed an investment firm called the TLC Group, a name whose initials he consistently refused to disclose. (Most observers agree that the most likely combination is “The Lewis Company.”) To staff the new company he turned to several old friends: Everett Grant, who had been with Price Waterhouse in public accounting; Thomas Lamia, a Washington D.C. lawyer; Cleveland Christophe, a Citibank executive; and his law partner Charles Clarkson. The TLC Group soon set out in hot pursuit of its first big game, the McCall Pattern Company.

McCall, a home-sewing products and publishing concern, was struggling under sagging sales and deep debt. Lewis purchased the company with a million dollars of his own money and a $24 million loan to the TLC Group from the First Boston Corporation, a New York investment banking firm. Lewis told Black Enterprise that although McCall had been overlooked by many Wall Street analysts, it was actually a prime candidate for acquisition: “A lot of people had written off [McCall] as not having much of a future, [but] the more I researched the facts the more I thought it had a great future, because its strongest asset was its most fundamental asset of all, and that was the people. It had a wonderful group of employees at the top, the middle, and throughout the organization who had excellent experience, who knew their business very well and who were committed to doing what was necessary to keep the company dynamic. The company had actually performed very well for a long period of time. When I delved into the facts, I decided that the fundamentals were actually quite good.”

The following year Lewis sold the McCall Pattern Company for $95 million, reaping an astonishing 90-to-l return on TLC’s initial cash investment. That dramatic coup assured Lewis a top ranking in Wall Street’s financial community and friendship with other Ronald Reagan-era power brokers, such as Drexel Burnham Lambert executive Michael R. Milken. Milken helped Lewis to engineer his next major transaction: the Beatrice takeover.

A multinational company with products as far-flung as Italian ice cream, German sausage, and Irish potato chips, Beatrice International’s operations are spread throughout Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Lewis liked the company for several reasons. As a food product concern not tied to the U.S. dollar, it seemed amply protected from both consumer buying cycles and the softening of the dollar in the late 1980s. And as a company with many separate operations, certain of those operations could be sold off to finance the deal—the typical leveraged buyout, in other words. This indeed is what transpired: TLC acquired Beatrice International for $985 million, then sold the Canadian operations to a Toronto firm for $235 million and the Australian operations for an additional $100 million. When the ink dried, Lewis found himself at the helm of a huge business empire located in all parts of the globe. The new boss let it be known that he would retain the hands-off managerial style he had used at McCall. “We rely on managers to understand their businesses,” he told Time magazine. “I want the people who work for me to look at challenges, roll up their shirt sleeves, and get to it.”

Lewis was well known before the Beatrice deal, but afterward he ascended to that sort of celebrity reserved for those who successfully manipulate vast quantities of money. He was not comfortable in the limelight, feeling that his accomplishments were not at all related to his race. The entrepreneur told Black Enterprise: “I’m always amused by people who talk about the overnight success of TLC Group. We’ve been banging away at this step-by-step for 20 years. I’m often disturbed by the notion of the so-called glass ceiling, but you know, glass can be broken. I’ve never liked hearing people say you can’t do this or you can’t do that. The point, though, is not to just say it. It’s important to be prepared to act and sacrifice, to accept [the fact] that if this is what you want, just wishing it would happen is not enough. You’ve got to follow through and take the necessary steps to make it happen.”

In the wake of the Beatrice acquisition, Lewis sold more assets in order to retire some of the conglomerate’s debt. By 1990, the trimmed-down company boasted $1.1 billion in annual sales from 15 operating units employing some 7,000 people, mostly in Western Europe. The size and scope of Beatrice assured Lewis the position of the most successful black businessman in America. Not everything went as planned, however. The TLC Group withdrew a public offering of stock in 1990 when Wall Street investors questioned the amount of profit to be reaped by the Group and the high price per share. Later that same year Lewis was served with two lawsuits stemming from his management of McCall Pattern Company. Two different McCall’s buyers accused Lewis of heaping debt onto that company, siphoning away key assets, and keeping misleading financial records—charges Lewis denied vehemently. In 1993, McCall’s was reorganizing after a Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceeding.

Lewis made philanthropy a part of his agenda for many years, donating generously to political candidates such as Jesse Jackson and private urban renewal programs. In 1992 he gave a $3 million grant to Harvard Law School for the establishment of the Reginald F. Lewis International Law Center, the first building at that university named after an African American. He also contributed a million dollars to Howard University and a sizable gift to his alma mater, Virginia State. Late in 1992 Lewis—who had remained trim and athletic throughout his career—discovered he had brain cancer. He managed to arrange for an orderly transition of power at TLC Beatrice, naming his stepbrother Jean Fugett, Jr., chairman of the company. Lewis died of a cerebral hemorrhage on January 19, 1993.

Several hundred people attended Lewis’s funeral at the Riverside Church in Manhattan on January 25, 1993. Among the mourners was longtime Lewis friend David N. Dinkins, mayor of New York. Dinkins told the crowd: “Reginald Lewis accomplished more in half a century than most of us could ever deem imaginable. And his brilliant career was matched always by a warm and generous heart.” Dinkins added: “It is said that ‘service to others is the rent we pay for space on earth.’ Reg Lewis departed us paid in full.”

Sources:

http://www.blackentrepreneurprofile.com/profile-full/article/reginald-lewis/

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Reginald_F._Lewis.aspx