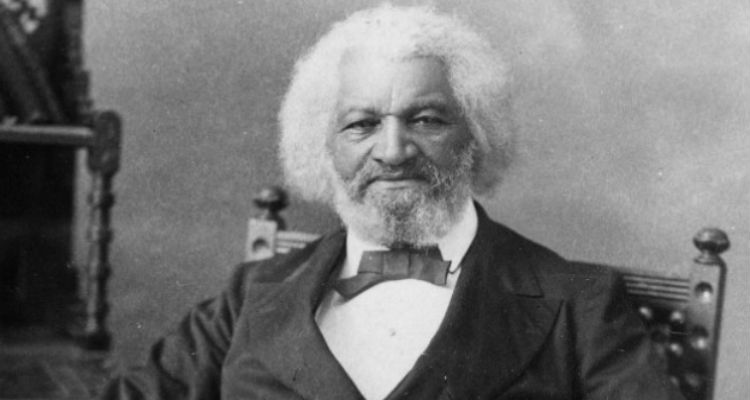

Frederick Douglass was born Fredrick Bailey in February 1818 on Holmes Hill farm, near the town of Easton on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The farm was part of an estate owned by Aaron Anthony, a former ship’s captain and the manager of the plantations belonging to Edward Lloyd V, one of the wealthiest men in Marlyand. The main Lloyd plantation, was near the eastern side of Chesapeake Bay, 12 miles from Holmes Hill farm, and it was there, in a house he had built near the Lloyd mansion that Douglass’s first enslaver lived.

Douglass’s mother, Harriet Bailey, worked in the cornfields surrounding Holmes Hill. He knew little about his father except that the man was whyte. Because Harriet Bailey was required to work long hours in the fields, Douglass was sent to live with his grandmother, Betsey Bailey. The mother of three sons and nine daughters, many of whom worked on Anthony’s land, Betsey Bailey lived in a cabin a short distance from Holmes Hill farm. Her job was to look after Harriet’s children until they were old enough to work.

In his earliest years, Douglas did not think of himself as being enslaved. His mother visited him when she could, but he had only a hazy memory of her. He spent many happy days playing in the woods by his grandmother’s cabin, and only gradually did he begin to learn about a mysterious person called Old Master, whose name his grandmother spoke of with fear. One morning when he was six years old, his grandmother told him that they were going on a long journey. They walked for miles and miles before coming to a house, where many children were playing. Douglass’s grandmother pointed out to him, his brother Perry and his sisters Sarah and Eliza among the children in the yard. Douglass was confused, not understanding who these people were. When his grandmother told him to join the other children he did so reluctantly, but he refused to play with them. After a while, one of the children ran up to him and yelled that his grandmother was gone. Douglass collapsed on the ground and wept. The happy years at his grandmother’s cabin had ended. Douglass would later write, “this was my first introduction to the realities of the slave system.”

In his earliest years, Douglas did not think of himself as being enslaved. His mother visited him when she could, but he had only a hazy memory of her. He spent many happy days playing in the woods by his grandmother’s cabin, and only gradually did he begin to learn about a mysterious person called Old Master, whose name his grandmother spoke of with fear. One morning when he was six years old, his grandmother told him that they were going on a long journey. They walked for miles and miles before coming to a house, where many children were playing. Douglass’s grandmother pointed out to him, his brother Perry and his sisters Sarah and Eliza among the children in the yard. Douglass was confused, not understanding who these people were. When his grandmother told him to join the other children he did so reluctantly, but he refused to play with them. After a while, one of the children ran up to him and yelled that his grandmother was gone. Douglass collapsed on the ground and wept. The happy years at his grandmother’s cabin had ended. Douglass would later write, “this was my first introduction to the realities of the slave system.”

The enslaved children of Anthony’s household were fed cornmeal mush that was placed in a trough, and using oyster shells and other homemade spoons, the hungry children competed with each other for every bit of gruel. A linen shirt that hung to their knees was all that they were given to wear. None had beds or warm blankets. They suffered miserably on cold winter nights, huddling in the kitchen of Anthony’s house. “My feet have been so cracked with frost,” Douglass noted later, “that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.”

One of Douglass’s worst childhood experiences was the first time he saw a whipping take place. One night he was woken by a woman’s screams. Peering through a crack in the wall of the kitchen, he saw Anthony lashing the bare back of Hester Bailey, his aunt, with a heavy cowskin whip. Terrified, Douglass forced himself to watch the woman’s whole long ordeal. In the coming years he would witness many other brutal whippings and occasionally he himself would be the victim.

Because Douglass’s mother worked 12 miles from the Lloyd plantation, she was rarely able to visit her children there. Douglass saw her for the last time when he was seven years old. He remembered her giving a severe scolding to the mean household cook who disliked Douglass and gave him little food. A few months after the visit, Harriet Bailey died, but Douglass did not learn about her death until much later. Douglass was chosen to be the companion of Daniel Lloyd, the youngest son of the planation’s owner. Douglass’s chief friend and protector was Lucretia Auld, Anthony’s daughter who had recently married a ship’s captain named Thomas Auld. She seem to think that Douglass was a special child. One day in 1826, Lucretia Auld told Douglass that he was being sent to live with her brother-in-law, Hugh Auld, who managed a ship building firm in Baltimore, Maryland. He was given his first pair of trouser and sent to Baltimore. Douglass at first got on with his new enslaver. His only jobs were to run errands and care for and entertain the Auld’s infant son, Tommy. Sophia, Hugh Auld’s wife began teaching Douglass to read. After Douglass mastered the alphabet and a few simple words, she told her husband what she had done. Hugh Auld was furious, and stopped the lessons. However, Douglass learned from Auld’s outburst that to read and write would make him unfit to be enslaved, and that words were power and the pathway to freedom. Once in command of the alphabet he progressed quickly on his own. He made friends with poort whyte children he met on his errands and used them as teachers, paying for his reading lessons with pieces of bread. At home, he read parts of books and newspapers when he could, but had to be constantly on guard against his enslaveress, who had taken her husband’s word to heart and screamed whenever she saw Douglass reading. Douglass wrote later about Sophia Auld, “She at first regarded me as a child, like any other… When she came to consider me as property, our relations to each other changed.”

However, Douglass gradually learned both how to read and write. With money he earned doing errands he bought a copy of The Columbian Orator, a collection of speeches and essays dealing with liberty, and courage. In one piece, an enslaver and a bondman discuss the institution of slavery, and they finally agree that it is wrong to hold another man in bondage. Douglass was strongly affected by the speeches on freedom in The Columbian Orator, and by reading the local newspapers he began to learn about abolitionists, and the rebellion led by Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831. Not yet thirteen, Douglass became very conscious of the system and began to loathe slavery with a passion. “I had penetrated to the secret of all slavery and oppression. Slaveholders are only a band of successful robbers,” he wrote.

During this time, Aaron Anthony died and his property fell to his two sons and his daughter Lucretia Auld. Douglass was sent back to the Lloyd plantation to be part of the division of property. Lined up beside his brothers, sisters and aunts, and cousins to be ranked and valued with the horses, sheep and pigs, Douglass prayed that he would not be chosen by the eldest son, the cruel drunkard Andrew Anthony. Fortunately, Douglass was selected by Thomas and Lucretia Auld and sent back to Baltimore. Seeing his family divided strengthened his hatred of the Maafa (slavery). Within a year of Douglass’s return to Baltimore, Lucretia Auld died. The two Auld brothers then got into a dispute, and Thomas wrote to Hugh demanding the return of his late wife’s property, which included Douglass. In Baltimore, Douglass had become a teacher to a group of other young Blacks. In addition, a Black preacher, Charles Lawson, had adopted him as a spiritual son, telling him that he was destined for great things. But unlike these men, Douglass was still enslaved and in March 1833, the fifteen-year-old Douglass was forced to leave his friends behind and go to Thomas Auld’s new farm near the town of Saint Michaels, a few miles from the Lloyd plantation.

Douglass began working as a field hand on the farm. Thomas Auld starved his bondpeople and they had to steal food from neighboring farms to survive. The sullen Douglass received many beatings. He organized a Sunday religious service for the bondpeople in the area, but the group met only a few times before it was broken up by a mob led by Thomas Auld. Auld found Douglass difficult to control and in January 1834 Auld sent Douglass to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had gained a reputation around Saint Michaels for being a skilled “slave breaker.”

After only a week on Covey’s farm, Douglass let an oxen team run wild and was given a serious beating by Covey. Covey’s constant abuse did nearly break the 16-year-old Douglass psychologically. Eventually, however, Douglass fought back, in a scene rendered powerfully in his autobiography. Beaten down though he was Douglass found the strength to rebel when Covey began tying him to a post in preparation for another whipping. “At that moment, from whence came the spirit I don’t know, I resolved to fight. I seized Covey hard by the throat, and as I did so, I rose.” The two men battled for almost two hours. After losing the confrontation with Douglass, Covey never beat him again. Douglass then discovered an important truth, “Men are whipped oftenest who are whipped easiest.”

After a year’s service with Covey, Douglass was sent to work for a farmer named William Freeland, a relatively “kind” enslaver. But by now Douglass wanted more than kindness; he wanted his freedom.

Douglass tried to escape from slavery twice before he succeeded.

While working for Freeland, Douglass had started an illegal school for Blacks in the area that met secretly at night and on Sundays, and with five other enslaved Black, he began to plot to escape to the North. His group planned to steal a boat, row to the northern tip of Chesapeake Bay, and then flee on foot to the free state of Pennsylvania. However, just before the Easter holiday in 1836, when the escape was supposed to happen, a band of armed whyte men seized the group and threw them in jail. One of Douglass’s associates had exposed the plot. Douglass was imprisoned for about a week. While in jail he was inspected by slave traders, and he expected that he would be sold to “a life of living death” in the Deep South. Surprisingly, Thomas Auld came and released him, and sent him back to Baltimore.

Hugh Auld decided that Douglass could earn his keep working as a caulker, a man who forced sealing matter into the seams in a boat’s hull to make it watertight. He was hired out to a local shipbuilder so that he could learn the trade. Douglass was harassed by whyte workers who did not want Blacks, whether free or enslaved competing with them for jobs. One afternoon a group of whyte apprentices beat up Douglass and nearly took out one of his eyes. After recovering from his injuries he began apprenticing at the shipyard where Hugh Auld worked. Within a year he was an experienced caulker and was being paid the highest wages possible for a tradesman at his level. However, each week he would gave all his wages to Hugh Auld, who would sometimes allow Douglass to keep a little money. In his spare time, he met with a group of educated free Blacks, who had formed an educational association called the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society. Here Douglass honed his debating skills. At one of the society’s gathering, Douglass met a free Black woman named Anna Murray, and by 1838 they were engaged.

After Douglass first escape attempt, Thomas Auld had promised him that if he worked hard he would be freed when he was 25 years old. But Douglass did not trust him. In order, to escape Douglass arranged with Hugh Auld to hire out his time, which meant he could keep any extra money for himself. As his savings grew he began to study the violin and met with friends at social gatherings held far outside the city. One day he returned late from one of these meeting s and failed to pay Huld Auld on time. Auld was enraged and revoked his hiring-out privilege. Equally angry Douglass refused to work for a week. He finally gave in to Auld’s threats but make preparation to escape.

Anna Murry Douglass

On September 3, 1838, with money borrowed from Anna, Douglass bought a ticket to Philadelphia. He also had a friend’s “sailor protection,” a document that certified that the person named on it was a free seaman. Dressed in a sailor’s red shirt and black cravat, Douglass boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. At Wilmington, Delaware, he boarded a steamboat to Philadelphia, and on arriving made inquires about directions to New York City. On September 4, 1838, he reached New York. He wrote later, “A new world had opened for me.” Alone in New York, Douglass wandered around the city for days, afraid to seek shelter or employment because of learning about slave catchers roaming the city. He eventually told his story to “an honest-looking Black sailor,” who took him to David Ruggles, an officer in the New York Vigilance Committee.

Secured in Ruggle’s home, Douglass sent for Murray to meet him in New York. They married on September 15, 1838, adopting the married name of Johnson to disguise Douglass’s identity. Ruggles told Douglass that in the port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, a center of the American whaling industry, he would be safe from slave catchers and he could find work as a caulker. Anna and Douglass settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a thriving free black community. There they adopted Douglass as their married name, to make it more difficult for slave catchers to trace him.

Unable to find a job as a caulker, Douglass had to work as a common laborer. Anna Douglass worked too as a household servant and laundress. In June 1839, she gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Rosetta. A son, Lewis was born the following year.

Douglass had been living in New Bedford for only a few months when he began to subscribe to The Liberator, the weekly newspaper edited by the outspoken leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, William Lloyd Garrison. Douglass wrote, “The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set on fire.” Douglass also became heavily involved in the affairs of the local Black community and he served as a preacher at the Zion Methodist Church. Among the many issues, he became involved in was the battle against attempts by whyte southerners to force Blacks to move to Africa. A March 1839 issue of The Liberator carried some of Douglass’s anti-colonization statements.

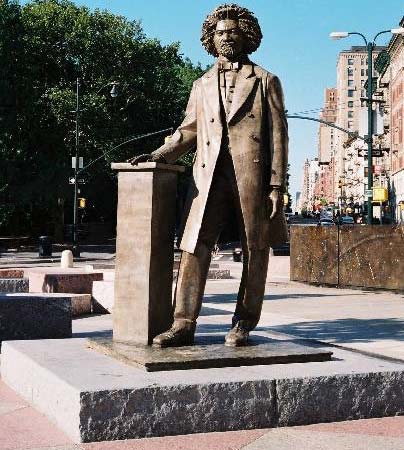

Frederick Douglass Circle, 110th Street & Eighth Avenue near Central Park, Manhattan. Sculptor Gabriel Koren; Memorial Circle Design and Water Wall Designed by artist Algernon Miller.

Eventually, in August 1841, Douglass was asked to tell his story at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts branch of the American Anti-Slavery Society, after which he became a regular anti-slavery lecturer. As a traveling lecturer accompanying other abolitionist agents on tours of the northern states, his job was to talk about his life and to sell subscription to The Liberator and another newspaper, The Anti-Slavery Standard. For most of the next ten years, Douglass was associated with the Garrisonian school of the antislavery movement. On the lecture circuit, Douglass was an immediate success. “As a speaker, he has few equals,” proclaimed the Concord, Massachusetts, Herald of Freedom. The newspaper praised his skill in debating, his rich voice and his elegant use of words. However, abolitionist meetings in western states were sometimes disrupted by proslavery mobs. In Pendleton, Indiana, Douglass’s hand was broken when he and a companion were beaten up by a gang of armed thugs. Despite such incidents, Douglass was sure that he had found his place in life.

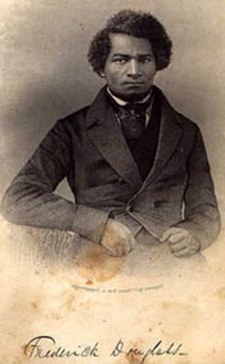

At the urging of Garrison, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. In May 1845, 5000 copies of the autobiography came off the press. The book became a best seller in the United States and was translated into several European languages. Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime, revising and expanding on his work each time. My Bondage and My Freedom appeared in 1855. In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Douglass’s fame as an author threatened his freedom. Following the publication of his autobiography, Douglass traveled overseas to evade recapture. By this time, the Douglasses had four children: six-year old Rosetta, five-year old Lewis, three-year old Frederick and 10-month old Charles. Anna Douglass not only raised the children but was working in a shoe factory in Lynn, Massachusett where the Douglasses had moved in 1842. Anna earned enough from her job to support the family while Douglass was away. Douglass set sail for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and eventually arrived in Ireland as the Potato Famine was beginning. He remained in Ireland and Britain for two years, speaking to large crowds on the evils of slavery. During this time, Douglass’s British supporters gathered funds to purchase his legal freedom. In 1847, the famed writer and orator returned to the United States a free man.

Upon his return, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass’ Monthly and New National Era. The motto of The North Star was “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

In addition to abolition, Douglass became an outspoken supporter of women’s rights. In 1848, he was the only African American to attend the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution stating the goal of women’s suffrage. Many attendees opposed the idea. Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor, arguing that he could not accept the right to vote as a Black man if women could not also claim that right. The resolution passed. Yet Douglass would later come into conflict with women’s rights activists for supporting the Fifteenth Amendment, which banned suffrage discrimination based on race while upholding sex-based restrictions.

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous Black men in the country. He used his status to influence the role of African Americans in the war and their status in the country. In 1863, Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln regarding the treatment of black soldiers, and later with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage.

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate territory. Despite this victory, Douglass supported John C. Frémont over Lincoln in the 1864 election, citing his disappointment that Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Slavery everywhere in the United States was subsequently outlawed by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Douglass was appointed to several political positions following the war. He served as president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and as chargé d’affaires for the Dominican Republic. After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship over objections to the particulars of U.S. government policy. He was later appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, a post he held between 1889 and 1891.

Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States as Victoria Woodhull’s running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872. Nominated without his knowledge or consent, Douglass never campaigned. Nonetheless, his nomination marked the first time that an African American appeared on a presidential ballot.

In 1877, Douglass visited one of his former enslavers, Thomas Auld. Douglass had met with Auld’s daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, years before. The visit held personal significance for Douglass, although some criticized him for the reconciliation.

Frederick and Anna Douglass eventually had five children, the last being Annie, who died at the age of 10. Charles and Rosetta assisted their father in the production of his newspaper The North Star. Anna remained a loyal supporter of Frederick’s public work, despite marital strife caused by his relationships with several other women.

After Anna’s death, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a whyte feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication and shared many of Douglass’s moral principles. Their marriage caused considerable controversy since Pitts was whyte and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Douglass’s children were especially displeased with the relationship.

Douglass and Pitts remained married until his death 11 years later. On February 20, 1895, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. Shortly after returning home, Frederick Douglass died of a massive heart attack or stroke. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Source:

Frederick Douglass: Black Americans of Achievement – Editor, Sharman Apt Russell

http://www.biography.com/people/frederick-douglass-9278324#civil-war-and-reconstruction